No Coincidence: Black Family Separations Then and Now

February 16, 2023

February 16, 2023

Author: Josie Pickens

“Night and day, you could hear men and women screaming … ma, pa, sister or brother … taken without any warning…People was always dying from a broken heart.” These were sentiments shared during a 1938 interview with Susan Hamilton, a woman still traumatized by the slave auctions she had witnessed as a child. Hamilton’s recollection offers some understanding of what Black families faced during enslavement– an incomprehensible level of pain, anger, confusion, and powerlessness. Sadly, when speaking with Black families who have had their children forcibly and involuntarily removed by the family policing system today, too little has changed.

The family policing system currently separates over 200,000 children from their families annually. Black children make up a disproportionate amount of those who experience family separations. Many of these children will never be reunited with their families due to their parents’ loss of parental rights. The family policing system, year after year, with little public knowledge or examination, perpetually tears apart Black families. This happens because the separation of Black families at the hands of the state has been normalized—a normalization that results from a societal refusal to acknowledge and reckon with a history of slavery, settler colonialism, and genocide.

As we continue to interrogate the family policing system and how it harms Black families, it is imperative to acknowledge the long history of Black family separations that sit at the root of how the United States moved towards “first world” nationhood and how it built its wealth. Not only was separating Black children from their parents profitable for enslavers, but the practice was also used as a mechanism of power, dominance, and control. This White supremacist violence laid the foundation for the maltreatment and exploitation that happens today in the modern family policing system.

The often-brutal family separations Black families endured during the era of chattel slavery were both broad and inescapable. According to historical evidence, as few as one-third and as many as two-thirds of Black children were separated from their families before chattel slavery was abolished. Recorded testimonies from the formerly enslaved chronicle a level of mental, emotional, and physical cruelty that seems incomprehensible—especially concerning what they and their children endured at the hands of enslavers and their agents. The intent of this inhumane treatment was clear: separating children from their families was one of the most malicious forms of punishment enslavers could enact against the enslaved. This kind of punishment forced the enslaved to comply with their enslavers and ensured that they would not attempt to escape or rebel.

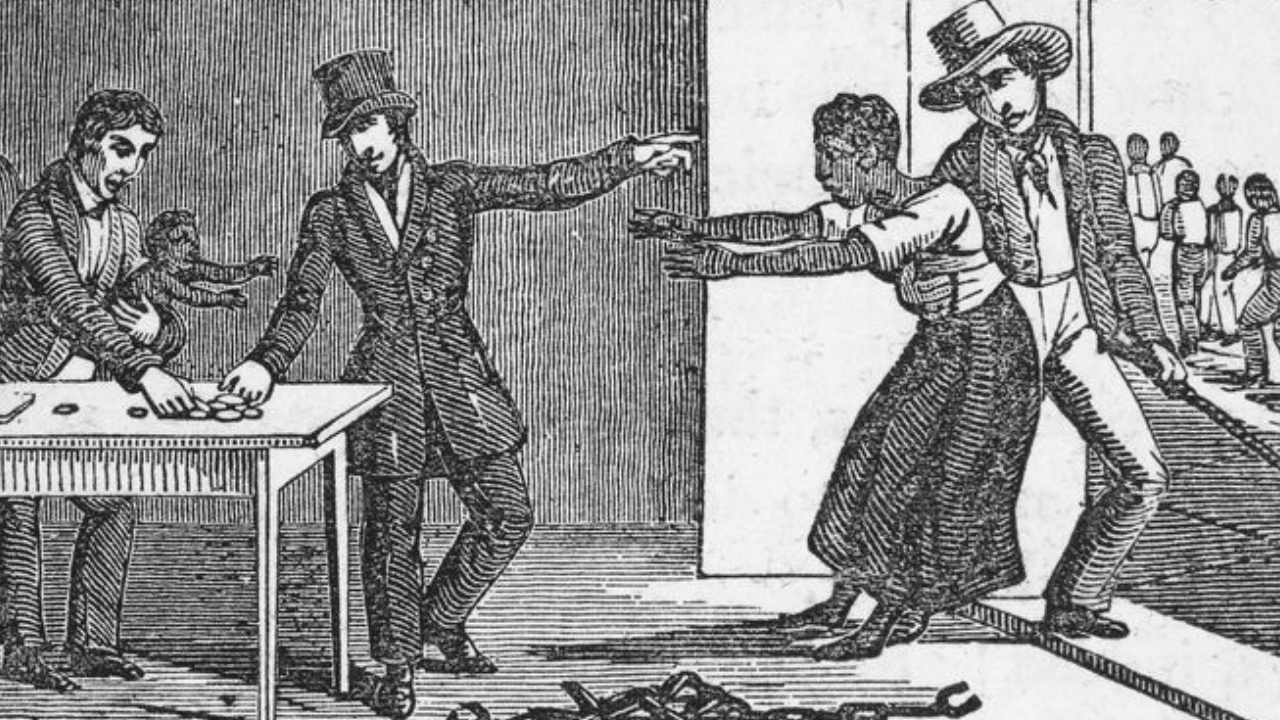

The ways in which enslavers forcibly removed Black children from their parents were so horrific and merciless that abolitionists fighting to end the institution of chattel slavery used images of Black children being ripped from their mother’s arms to radicalize Whites toward championing abolition. Although freedom, by name, came for Black people after the Civil War and through the passing of the 13th Amendment, many continued to suffer under Black Codes that, essentially, created a system of laws and statutes that sanctioned more forced and unpaid labor from Black people. Although the 13th Amendment stated that the formerly enslaved would be subjected to “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude,” a loophole was present that negated much of the work of abolitionists.

As Black Codes were ratified throughout the U.S., the formerly enslaved could be forced to continue what was ultimately slavery by another name if they were accused of a crime. Black Codes intentionally limited the freedoms of Black people as these laws and statutes often denied them voting access, created systems of segregation and further oppression, and restricted employment opportunities—which would have helped Black people build wealth and hence be able to better provide for their families and build their communities. If Black people were guilty of defying any of the Black Codes put in place, they were often punished with long-term imprisonment, which provided the state, and more particularly Whites, with free labor. These excessive punishments are what set the foundation for what we now understand to be the racist practice of mass incarceration. Another point rarely considered when discussing the history of family policing is that Black codes were also utilized to force apprenticeship, or indentured servitude, on Black children against their parents’ will if those parents were determined to be unfit or unable to adequately care for their children.

As Black Codes, and all the harm the laws and statutes perpetuated against Black people began to be challenged, Jim Crow laws were soon enacted and upheld by both state and federal governments. Jim Crow laws continued to make segregation legal in employment, housing, schools, and more. This meant that Black individuals, families, and communities continued to be oppressed, exploited, and demoralized to maintain White dominance and White power. Segregation upheld by Jim Crow laws made access to wealth building through employment, home ownership, and equitable education tedious and widely unattainable for most Black people. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, supposedly passed to address issues related to equity and access, vowed to end segregation and, thus, systematic racism but did not live up to its promises.

Black people continue to suffer because of structural racism and a lack of access to fair and equitable housing, employment, education, and healthcare. Black people, families, and communities continue to be both under-resourced and overpoliced—including policing maintained by the family policing system. Today, more than half of Black children are investigated by the family policing system. Black children are twice (sometimes three times) as likely to be separated from their families than White children. None of this is by coincidence. The surveillance, regulation, and separation of Black families is a significant component of U.S. history. The only difference between family separations experienced today and family separations experienced in the past is that today’s separations are presented as benevolent interventions.

At upEND Movement, we fight for the abolition of the family policing system because we understand that any system rooted in capitalism, racism, and White dominance cannot be reformed. Instead of reform, we champion reparations for the descendants of those enslaved, a more equitable distribution of wealth and resources for Black people, and the handing over of power to Black people, Black families, and Black communities so that systems like the family policing system need not exist.

Much more on the racist history of family separations in the United States can be found in Alan Dettlaff’s upcoming book, “Confronting the Racist Legacy of the American Child Welfare System: The Case for Abolition”, to be released by Oxford University Press this Fall. Thank you to Alan for providing an early look at several chapters from this book which served as a resource for this blog.

Image Citation: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. “Black Mother being separated from her baby” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1862.