Reclaiming Safety for Children of Parents with Disabilities

May 20, 2025

May 20, 2025

Angela Burton and Alan Dettlaff

In our introductory essay to this series, Reclaiming Safety, we committed to apply an abolitionist lens to envisioning a world free of family policing, where all children and families have everything they need to be safe and thrive within their homes and communities, and where a government system that forcibly separates children from their parents is so abhorrent as to be unthinkable: “In this vision, resources are devoted to supporting the safety and well-being of children, families, and communities, and these communities work intensely, invest heavily, and collaborate creatively to ensure children are safe and families thrive.” We stressed that “abolition is not merely about ending the family policing system; it is about creating societal conditions that render such a system obsolete.” In short, strengthening and creating strong social connections and making supportive resources readily available are central to the family policing abolition project.

With the understanding that “child protection” and “child safety” as defined in law, policy, practice, and public opinion are complex and multi-faceted, in this series we focus on specific contexts often cited as barriers to engaging with abolitionist ideas – physical and sexual abuse, intrafamilial violence, parental drug use or abuse, and parental disability, whether physical, intellectual, or mental. In contrast to the prevailing reactive, carceral, system-centered approach to child safety, we take a dynamic, human-centered perspective, along with Mariame Kaba and Andrea Ritchie, who remind us that

“Abolition also requires us to unpack the notion of safety itself. While safety is a basic and universal human need, it doesn’t have a universal and singular definition. . . We also need to let go of the idea that safety is a state of being that can be personally or permanently achieved. Safety isn’t a commodity that can be manufactured and sold to us by the carceral state or private corporations. Nor is safety a static state of being. Safety is dependent on social relations and operates relative to conditions: We are more or less safe depending on our relationship to others and our access to the resources we need to survive.”

Viewing safety through this relational, collective care lens, family policing abolitionists consider questions such as: What principles, processes, and support mechanisms can empower individuals, families, and communities to autonomously identify and implement what is needed for safety, healing, and preventing future harm? What are effective responses to incidents or patterns of intrafamilial harm? What does justice look like in the context of intrafamilial harm?

Examining these critical questions is necessary to clarify, refine, articulate – and put into practice – our vision for a society where families have what they need to thrive and keep children safe, and where a range of easily accessible and effective responses are available to address harm when harm occurs.

by Charisa Smith

by Charisa Smith

In this paper, Charisa Smith uses an abolitionist framework to confront questions about safety and well-being for children of parents living with disabilities. The term “disabilities” is used here to comprise the full spectrum of physical, cognitive, and mental health challenges. According to a 2024 U.S. Surgeon General report, forty-one percent of U.S. parents are “so stressed they cannot function” most days, while nearly fifty percent are completely overwhelmed by stress– primarily due to the lack of a social safety net to support the broad needs and lives of parents and their families (Surgeon General’s Advisory). Yet, while parents struggle regardless of their disability status, the family policing system intervenes in families with disabilities at higher rates and treats them more harshly than others. Using hypothetical scenarios based on real life situations (and modified for privacy reasons) to examine abolitionist interventions in practice as key steps forward, the author highlights strength-based, individualized, and supportive strategies that can help secure children’s safety while respecting family integrity and autonomy, and maintaining, strengthening, and empowering authentic relational connections and responsive collective care.

In general, the group parents with disabilities is composed of individuals who each have a certain “physical or mental” challenge or condition that impacts at least one of their “major life” activities when the challenge or condition is active.1 Major life activities may include performing manual tasks, seeing, hearing, being mobile, learning, communicating, and performing certain types of work. Disability should be broadly interpreted, and always with the understanding that it intersects with other aspects of identity, as parents targeted by the family policing system are typically members of marginalized groups and may lack access to care, support, and even the ability to define or recognize their disability and its impacts. Indeed, within the diverse communities of people with disabilities, there is a vital and ongoing conversation about the very language used to describe people with disabilities.2 Further, parents with disabilities tend to face widespread, daily challenges in their communities because schools, doctor’s offices, public transportation systems, and other locations throughout the United States remain largely inaccessible to individuals with physical disabilities, as well as unsuitably adapted for those with intellectual and learning disabilities.3

Stereotypes about parents with physical or mental health challenges undergird the family policing system’s presumption that parents with disabilities are inherently dangerous to their children. Taking to the extreme the idea that children are presumptively unsafe in the care of parents with disabilities, some discriminatory state laws4 tragically still mention conditions like an intellectual disability (ID)5 as potential grounds for termination of parental rights.6 These damaging stereotypes are extremely unfounded. Research reveals that children of parents with a wide range of disabilities “generally have ‘typical development and . . . often enhanced life perspectives and skills.’”7

In a truly transformed future, abolitionists envision communities, support systems, and redistributed resources and power addressing the trauma, scarcity, and pain that tend to be underlying reasons for situations triggering state intervention in the first place. Indeed, “trauma can be both an antecedent to and result of involvement in the family regulation system,” and both courts and copious research demonstrate that removing a child from their parent can be “more damaging to the child than doing nothing at all.”8

Overall, this paper argues that an abolitionist response to challenges and crises experienced by families where a parent has a disability should always begin on an individualized level, centering the articulated needs, strengths, and goals of the child and parent. Individualized accommodations for parents with disabilities and their children is both the most clinically informed and legally advisable approach.9

Although gaining a national snapshot of parent disabilities in the United States family policing system is difficult, statistics from all state and national studies demonstrate that parents with disabilities and their children are disproportionately represented in the system and are treated unjustly at every stage in the process. Children of parents with ID alone are over three times as likely to have their rights to their parents and families terminated than others, and their rates of family separation are around 80% higher than children of non-disabled parents.10 A national survey recently revealed that parents with mental disabilities were eight times more likely to have contact with the family policing system than parents without mental disabilities, and twenty-six times more likely to have their child removed.11

An abolitionist approach to safety and well-being for children of parents with disabilities may be counter-cultural, though not radical as some may think. If anything, an abolitionist approach to safety and well-being forces brutal honesty on the part of people who claim to care about children and families. Persistent state violence in the form of unwarranted family separation, surveillance of marginalized families, and disparate treatment of parents with disabilities is one of today’s most under-recognized civil rights issues12 because of what I have previously called the empathy gap.13 The empathy gap is a double standard evident throughout history and at present, through which the American public, policymakers, legal systems, and the mainstream media perceive and respond to similarly situated children and families differently, merely based on their racial or ethnic identity. A wealth of behavioral psychology research and polling supports the existence of this double standard in social compassion.14

Though racism in the United States is hardly a surprise, it is crucial to acknowledge that the empathy gap operates similarly with regard to parents with disabilities. When it comes to parents with disabilities and their children, moderate and progressive individuals who care about child and family wellbeing seemingly misunderstand an abolitionist approach as somehow extreme or even dangerous. However, considering the influence of the empathy gap, this approach simply asks: “How would this family’s problems be handled if they were white? Would they have been surveilled at all?”

The opioid crisis provides one robust example of the empathy gap at work. In 2017, the U.S. Surgeon General declared a nationwide public health emergency, which, according to the National Institutes of Health, was the result of “use and misuse of opioids, opioid use disorder, overdose deaths, and lack of effective pain management.” Extensive evidence from courts, media outlets, and national polling reveal that throughout the opioid crisis parents with opioid dependence received an outpouring of compassion, second chances, and relatability in the public mindset.15 This compassionate response to parents with opioid dependence is significant in a discussion about parents with disabilities. According to the U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, around 64% of individuals with any type of opioid use disorder (parents included) have an underlying mental health condition and are self-medicating for that underlying disability.16 Through media coverage of the opioid crisis, the public began to personalize the concepts of mental health challenges, substance misuse, and the everyday challenges of parenting in a nation without an adequate social safety net. Humane legal system programs were specifically created to keep adults with opioid dependency away from courts and jails, to help them maintain their community ties through substance abuse treatment programming attached to parenting programs, through re-entry services, and through other localized and strengths-based community-based supports.17 There was also heightened interest in civil rights issues in child welfare cases specifically focused on opioids.18

Although a significant segment of opioid users are people of color, in the U.S. mindset, opioids are largely still coded as “white” in contrast to crack cocaine for example, which is consistently racially coded as “Black.”19 Many white Americans could more easily empathize with a parent who became dependent on opioids because they could more easily see that person as their friend, their sibling, or someone like themselves. In contrast, however, empathizing with a Black parent targeted by the family policing system for something as minor as marijuana, let alone for a mental health issue, can still feel more challenging. It is therefore important to highlight best practices that guide abolitionist approaches regarding parents with disabilities.

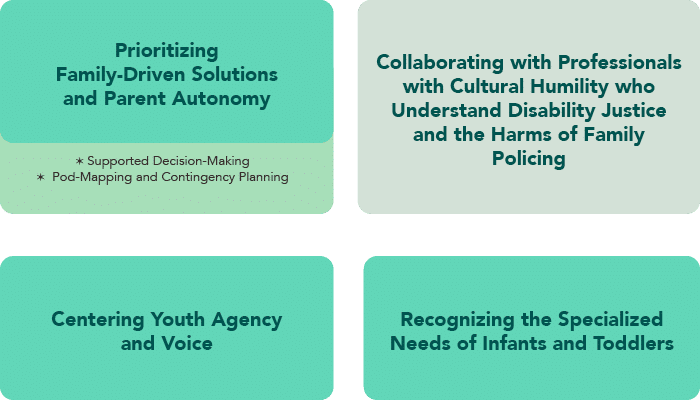

Abolitionists encourage baseline best practices in work with parents with disabilities that starkly differ from current family policing approaches. Below are some principles and mechanisms that support an abolitionist approach.

Abolitionists resist the notion that the state can lead a family’s own response process–even when a serious crisis calls for medical support–because the state’s cookie-cutter responses cannot address complex, infinite private life circumstances and nuanced cultural concerns, but instead inflict new violence or trauma upon families.20 Best practices of international human rights and behavioral health literature emphasize how each family is itself a unique ecosystem that serves its own function in society and deserves preservation and protection from intrusion.21 By virtue of their basic dignity, each family deserves empowerment to define their own needs, strengths, and wellbeing. That in turn avoids the short and long term harm to children and adults caused by unnecessary separation (and the ripple effects of societal impact upon the education system, the health system, and other arenas).22

Supported Decision-Making

Asking the reader to put themselves in the shoes of the parent instead of “othering,” pathologizing, or demonizing parents with disabilities, this paper explores ways to ensure that parents and children have direct access to necessary and beneficial resources, and that parents with cognitive disabilities have autonomy (and supported decision-making23 when necessary) to make choices for themselves and their children. As one proven approach that facilitates autonomy, supported decision-making is a “well recognized practice by which people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are able to make their own decisions with the support of trusted persons in their lives and retain all their legal and civil rights. . .[and is]. . .useful and available for” diverse decision-makers.

Pod-Mapping and Contingency Planning

Further, strategies like Pod-mapping and the broader frame of transformative justice that it is linked to, can create more connected communities centering disability justice and recognizing the inherent intersectional identities of families along race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and other key cultural axes.24 Specifically, Pod-Mapping is an action developed by disability activist Mia Mingus, which involves taking stock of one’s own self-care community. Originally conceptualized as a group of people who you can go to if violence, harm, or abuse has happened to you, if you caused harm, or if you have witnessed harm, Mingus explains that “pods can be used in a myriad of different contexts, far beyond acute harm and violence.”

“Pods is a simple concept with an endless amount of uses and applications. Pods was a way to make words such as ‘community’ and ‘support’ more concrete and pragmatic. In this way, pods can be relevant to any situation where support is needed. A pod relationship is a specific type of relationship, just like many other common types of relationships such as friend, co-worker, family or neighbor. While none of these relationships are mutually exclusive to each other, the same can be said for pod people. Your pod may include your friends, partners, neighbors or co-workers or it may not. In general though, pod people are often those you have some kind of relationship and trust with, even if it is not the deepest relationship and trust.”

There are various types of pods – the most common type of pod is a “general pod,” consisting of people who will be available in times of need or crisis, or simply to help with everyday needs such as access, childcare, emotional support,or transportation. Emergency/Crisis Pods can be established to plan for traumatic events before they happen to help lessen panic and chaos. For example, “[m]any people built pandemic pods at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic to help with things such as grocery shopping, checking in on elders, high-risk neighbors and loved ones, and being able to socialize with others in a safe way.”

By taking stock of who in their life they actually have a trusted, respectful, and reciprocal relationship with, and creating contingency plans in advance, parents with disabilities and their children will be in a better position to respond effectively when trouble arises, rather than resorting to the vague response that “community” (as opposed to status quo systems) will help in an emergency.25

While “[e]mergency and crisis are a place where local pod people can be especially critical,” in situations that require the use of a clinician, it is important to collaborate with professionals with cultural humility.

As discussed above, contingency planning with parents with disabilities and their children should be done in advance of any crisis situations. It is crucial that emergency and crisis planning include trusted professionals with cultural humility who understand disability justice, and who recognize the harms that the family policing system typically causes. The state and others currently use family policing to address parents’ poverty or lack of access to services, and poverty is pervasive among parents with disabilities,26 so a threshold inquiry should be whether an incident or situation even poses any risk or danger to a child whatsoever.

The vast majority of reports to child abuse and neglect hotlines (84%) are ultimately determined not to constitute maltreatment. (ChildTrends, 2024). Seventy-four percent of reported maltreatment cases involve allegations of neglect (failure to provide some necessity for a child) rather than affirmative abuse (ChildTrends 2024), and disadvantage gets conflated with parental wrongdoing.27 These statistics strongly suggest that the overwhelming majority of situations typically reported to CPS may require, if anything, nothing more than a friendly visit from a supportive family member, friend, or community member rather than a clinician or other professional in the first place.

Having the child in the driver’s seat as much as developmentally and feasibly possible is key in abolitionist approaches. Youth should be central to any planning and decision-making process, including contingency planning and the vetting of professionals to be utilized by the family. Abolitionists acknowledge that threshold issues do arise where a parent is unable to discern that risk or danger exists, a parent loses the ability to perceive indications of risk or danger arising, or where they are unable or unwilling to get help. It is still crucial to center the child’s voice in such situations when a child is verbal, however. Supportive adults should listen to the child’s agency, voice, wishes, and goals and enable them to play a key role in developing and implementing plans for their safety.

Importantly, infants and toddlers are in particular need of abolitionist solutions.28 An abolitionist approach recognizes what copious studies now demonstrate: that children under the age of three who are taken into the foster system endure one of the most abrupt, harmful “disruptions of critical attachments that are essential to this formative stage of brain development” due to being separated from their parent, regardless of the reason. The mere fact of forced separation alone leaves a child under age three “at great risk for lifelong impairments.”29 Because very young children (under age three) do comprise a significant and growing portion of foster placements, and because those inquiring about abolitionist perspectives often ask about young children, this paper will discuss such scenarios and promising program models as building blocks for a path forward.

Nine year old Tarlon had been happy at home for several months after staying with cousins about forty minutes away. His mom, Rita, was now on a much better medication for her Bipolar Disorder30 after having a psychotic episode31 and a brief hospital stay. It had taken a while for Rita to try different medications. Since no relatives live close by, during the time Rita was figuring out her medication regimen a mental health nurse home visitor would drop by to provide daily support to Rita and Tarlon. Occasionally, Ms. Sanders (closest neighbor) would babysit overnight when Rita expressed signs of stress that her therapist helped her outline with Tarlon’s input in some sessions and in parent-child play therapy.

Nine year old Tarlon had been happy at home for several months after staying with cousins about forty minutes away. His mom, Rita, was now on a much better medication for her Bipolar Disorder30 after having a psychotic episode31 and a brief hospital stay. It had taken a while for Rita to try different medications. Since no relatives live close by, during the time Rita was figuring out her medication regimen a mental health nurse home visitor would drop by to provide daily support to Rita and Tarlon. Occasionally, Ms. Sanders (closest neighbor) would babysit overnight when Rita expressed signs of stress that her therapist helped her outline with Tarlon’s input in some sessions and in parent-child play therapy.

One Saturday at a street fair, Tarlon notices some signs in Rita’s behavior that worry him, and thinks his mom may have stopped taking medication. He remembers that she mentioned skipping a doctor’s appointment because her boss wouldn’t give her the day off and she needed to pay bills. Tarlon is terrified he might get taken away from his mom. She is the only person who loves him deeply, understands his own quirks, knows the type of foods and games he likes, gets his silly jokes, and knows the signs that he himself may be extra-sensitive with his diagnosed sensory needs. She is always tuned-in to give him a quiet hug.

In the status quo environment, Tarlon would not feel safe telling anyone about Rita’s behavior because the state would almost certainly begin a punitive investigation that could result in his removal and jeopardize Rita’s parental rights altogether, all without any input from Tarlon. However, an abolitionist approach does otherwise. In particular, this abolitionist approach is vastly distinct from status quo approaches because it centers youth agency and facilitates Tarlon’s own ability (in a developmentally appropriate manner) to make decisions about the outcome of his family’s situation. Unlike status quo approaches, this abolitionist approach is less likely to cause Tarlon lingering trauma or shock, even as his mother experiences mental instability.

When home from the fair, Tarlon can choose to do one of several things to respond to his situation. As best practices recommend, Tarlon himself was trusted and given the autonomy to help map out these options along with specially trained adults who discussed the importance of both him and his mom being safe and well. In that planning process, Tarlon felt heard because he got to speak to adult and pediatric mental health specialists both in the comfort of Rita’s presence, and on his own with a supportive, neutral advocate from his community.

OPTION 1: Tarlon can tell his mom that he is worried she may not be taking her medication, and see how she responds. OR, If Tarlon does not feel saying this directly to his mom is a good idea, he can take one of the steps:

OPTION 2: Go see if Ms. Sanders is at home, or call Ms. Sanders’ cell phone. Ms. Sanders will convey the information to Rita as soon as possible. (Second or third, etc., designated and agreed-upon safe neighbor would be alternatives if Ms. Sanders isn’t reachable within a time span Tarlon is comfortable with); OR

OPTION 3: Use Rita’s cell phone (Tarlon’s if he has one, or the phone of the safest adult nearby) to contact one of the designated, agreed-upon neighbors or other adults. In turn, one of them will contact Rita’s nurse visitor to check in with her and see what is further needed.

In addition to informing an adult about the issue on the surface, Tarlon can tell them or his mom that he’d like extra support through any of the following:

Nineteen-year-old Lorna gave birth to her daughter Marie four months ago and is raising Marie alone after she decided to take a break from Marie’s father, who tended to be violent at times. Lorna has felt extremely depressed, useless, and sluggish since Marie’s birth. Lorna also just can’t stop crying and can’t shake the thought that she’s not a good enough mom for Marie. Friends stop by and adore Marie, bring gifts or food, and they try encouraging Lorna’s mood. Family members also don’t understand how worthless she feels. Selene (Lorna’s own biological mother) acts grandmotherly now, but Selene couldn’t even be located until a couple years back. Where was Selene as a parent when Lorna herself was in foster care, coping with her childhood Anxiety Disorder32 and panic attacks all on her own, sometimes in an abusive foster home? Now, everything is a struggle…just finding Marie’s little hat when a breeze comes through the apartment…trying to make a cup of coffee. Breastfeeding has been a nightmare, Marie usually won’t sleep more than a few hours (so neither can Lorna), and the thought of buying formula makes Lorna want to put Marie into a basket at the firehouse steps for someone rich to rescue her baby. Then Lorna could just disappear. Lorna hasn’t taken any anxiety medication in over a year due to pregnancy and breastfeeding, and she is unmotivated to find past phone numbers, let alone try public transit for an appointment with a newborn. Lorna knows about Postpartum Depression, and is pretty sure she is in the middle of a deep Postpartum Depression33 spiral with baby Marie caught up in it all. Things seem hopeless.

Nineteen-year-old Lorna gave birth to her daughter Marie four months ago and is raising Marie alone after she decided to take a break from Marie’s father, who tended to be violent at times. Lorna has felt extremely depressed, useless, and sluggish since Marie’s birth. Lorna also just can’t stop crying and can’t shake the thought that she’s not a good enough mom for Marie. Friends stop by and adore Marie, bring gifts or food, and they try encouraging Lorna’s mood. Family members also don’t understand how worthless she feels. Selene (Lorna’s own biological mother) acts grandmotherly now, but Selene couldn’t even be located until a couple years back. Where was Selene as a parent when Lorna herself was in foster care, coping with her childhood Anxiety Disorder32 and panic attacks all on her own, sometimes in an abusive foster home? Now, everything is a struggle…just finding Marie’s little hat when a breeze comes through the apartment…trying to make a cup of coffee. Breastfeeding has been a nightmare, Marie usually won’t sleep more than a few hours (so neither can Lorna), and the thought of buying formula makes Lorna want to put Marie into a basket at the firehouse steps for someone rich to rescue her baby. Then Lorna could just disappear. Lorna hasn’t taken any anxiety medication in over a year due to pregnancy and breastfeeding, and she is unmotivated to find past phone numbers, let alone try public transit for an appointment with a newborn. Lorna knows about Postpartum Depression, and is pretty sure she is in the middle of a deep Postpartum Depression33 spiral with baby Marie caught up in it all. Things seem hopeless.

One chilly October night at 11:55pm Lorna starts making the firehouse plan and can’t get it out of her mind. Lorna wants Marie to be found on the firehouse steps immediately, but she also doesn’t want to be seen herself. Lorna can’t take it anymore and is beside herself, crying hysterically. Hungry baby Marie matches mom’s hysterical cries. Lorna is not sure if she should run out of the house alone, with baby Marie, or do something worse.

In the status quo environment, Lorna would probably not feel safe talking to a medical or mental health professional in this moment, let alone bringing her baby there, because the state would almost certainly separate them. However, an abolitionist approach does otherwise:

OPTION 1: Lorna remembers the plan she put in place with Dr. Riley. Dr. Riley is a general practitioner who works with adults, associated with the medical practice where baby Marie has a pediatrician. The practice has a reliable 24 hour emergency on call system. Lorna and Dr. Riley worked out a plan where until Lorna can find more mental health support, she could rely on Dr. Riley to help her in an emergency. Lorna collects herself enough to stop sobbing, drink some glasses of water and call the on-call line, asking for Dr. Riley. She is told to leave a message, and that she will receive a return call within 20 minutes. As discussed, Lorna says she needs Dr. Riley to connect her with support because her new baby has a pediatrician practice, and she is having mental health challenges tonight herself. After 17 agonizing minutes where Lorna hears baby Marie’s shrieks and cries but is determined to hang on, Lorna receives a call from Dr. Arnold who is the substitute for Dr. Riley. Dr. Arnold has Dr. Riley’s notes about Lorna and baby Marie’s plan, and he is able to link Lorna with a nearby 24-hour mental health clinic that serves new mothers in Postpartum crises. Lorna confirms that she has car fare to get to the clinic, and that she can contact someone to stay with baby Marie in the meantime. Lorna feels slightly relieved even if overwhelmed. Lorna charges her phone and contacts her mother, Selene, along with several other relatives and friends. Selene is the first to volunteer to stay at Lorna’s apartment with baby Marie, and to help facilitate or discuss ongoing feeding and breast pumping options.

OPTION 2: Lorna finds the strength to knock loudly on the neighboring apartment door. Neighbor Trini hears baby Marie crying and comes to the door right away. Trini’s partner Dan is also awake, appears in the doorway looking concerned in a matter of moments, and invites Lorna to sit on the couch. Lorna knows Trini and Dan can be trusted, and she has told them before how much she appreciates their stopping by to check on her sometimes since she’s been living on her own with the baby. Although Lorna is very scared of all her extreme feelings, seeing their caring faces and hearing the voices of people she knows makes her feel much better. Eventually, Trini helps calm baby Marie down, and Trini and Dan both listen to Lorna hyperventilating saying she is “out of it. . .it’s all just too much. . .” After they ask about Lorna’s previous mental health providers, they try to soothe Lorna and look them up. Trini and Dan suggest that Lorna and Marie stay with them overnight, and Lorna agrees. The next day, Trini and Dan connect Lorna with her previous clinician for immediate medication and some ideas for talk therapists, and they help to ensure that friend or relative stays at Lorna’s apartment for the next couple days until more arrangements can be made.

Within a week, Lorna’s mom Selene has helped Lorna enroll in WeCare, a home visiting program specifically focused on decreasing stress levels in parents of infants—especially mothers experiencing mental health crises, and those with histories of trauma like Lorna’s time in foster care. Selene mentions that seeing Lorna receive help with baby Marie may be a fresh start for the two of them, and that she wants to be a good grandma as well as a better mom. WeCare involves a home visit of 60 to 90 minutes twice a week at first, and then once a week for up to a year if needed, with flexibility according to Lorna and baby Marie’s needs. The mental health clinician helps Lorna find her most authentic ways to care for, relate to, and play with Marie, while also providing a brief respite at times. All this ultimately helps Marie’s infant development flourish and gives Lorna newfound self-esteem, empowerment, and connection through family. Lorna particularly enjoys creating innovative play spaces in her own home environment. Programs like WeCare have been proven to improve parent mental health and executive functioning, reduce maltreatment and involvement with family policing systems, and decrease parent stress.34

Ralph is a loving dad who capably meets his three-year-old Shane’s needs. Ralph occasionally has trouble remembering things such as dressing Shane for the weather when the seasons change, or selecting the healthiest foods instead of the foods he finds most enjoyable. Ralph especially loves to bake cookies for Shane. Ralph was diagnosed in childhood with an intellectual disability and a learning disability.

Ralph is a loving dad who capably meets his three-year-old Shane’s needs. Ralph occasionally has trouble remembering things such as dressing Shane for the weather when the seasons change, or selecting the healthiest foods instead of the foods he finds most enjoyable. Ralph especially loves to bake cookies for Shane. Ralph was diagnosed in childhood with an intellectual disability and a learning disability.

One cold, rainy Monday afternoon at daycare pickup time, a social worker wants to meet with Ralph because she is upset that Shane is wearing a t-shirt, thin pants, and thin sneakers that get wet in the rain. She mentions that Shane also did not have a sweater or rain jacket in his daycare bag that morning. Ralph wonders if this scrutiny is because his family is Black. Shane’s classmate Lyla is in a short sleeve princess dress and no one said a word. Lyla’s family is white and lives in a better neighborhood.

In the status quo environment, the social worker may consider Shane’s lack of seasonal clothing to be neglect and may use Ralph’s disability as grounds for making a report to the child abuse hotline. An abolitionist approach does otherwise:

As it turns out, the social worker, Eliza, was in a particularly bad mood about an incident in another room and just wanted to talk with Ralph about making sure that his family gets all the resources they need as the weather changes. As a licensed social worker, Eliza is required by law to make a report to the child abuse hotline if she suspects or has reason to believe that a child has been abused or neglected.35 However, understanding the harms of the family policing system and well aware that this system is not equipped to provide families like Ralph and Shane with adequate resources and supports, Eliza has adopted the “mandated supporter” approach.36 Eliza has connections with community-based programs and an advocacy group for inclusive caregiving and disability justice. Eliza asks if Ralph is okay scheduling another time to talk about how the daycare center can best help him and Shane feel included in the daycare center’s programming. For example, Eliza asks, Does he consider their emails to be clear enough for him? Are the paper announcements they post around the center helpful? Does he need any extra support setting rules or boundaries with Shane in transition times to and from daycare? Or just understanding toddler development? Would it help to have more explanation from Shane’s daycare teachers if something isn’t clear? Ralph chuckles that he doesn’t use email and isn’t always able to catch posted signs the way they are worded, so more support explaining would be great. Ralph mentions there are always money issues living in this city, so help with winter coats would be great, but also he just needs to give his own self time remembering things because Shane has sweaters at home. Eliza suggests that it’s always a good idea to have some extra clothes in each child’s cubby at their daycare center.

Eliza and Ralph make a plan to talk on Friday about boosting his support network as well, since parents with intellectual disabilities thrive more and build skills with a circle of support, or care web.37 Ralph is particularly struck when Eliza explains the concept of a care web to him. He agrees that people always assume people with disabilities are the ones needing help, but Eliza says that in the idea of care webs, no one is assumed to need charity, it’s a mutual give-and-take. Here, Shane brings the best cookies she’s ever had to daycare every day so clearly there is something Ralph has to share as well! Eliza also asks if Ralph is interested in talking with other parents that face challenges for support and also to share how he manages certain things so well. Ralph says he would be very interested.

Janice is a mother of three who has mobility challenges and uses a wheelchair. Her children— Kyle, Reena, and Izzy, are ages eleven, six, and three, and seem to constantly rip the house apart while yelling at the top of their lungs. Janice is used to the noise and mess, but her partner Samuel works long hours and is rarely home to watch the children together. Despite all the work, bills are piling up and it is difficult to make ends meet. Both Janice and Samuel are loving, caring parents to the children. Stress and occasional loud, dramatic arguments between them are also a challenge.

Janice is a mother of three who has mobility challenges and uses a wheelchair. Her children— Kyle, Reena, and Izzy, are ages eleven, six, and three, and seem to constantly rip the house apart while yelling at the top of their lungs. Janice is used to the noise and mess, but her partner Samuel works long hours and is rarely home to watch the children together. Despite all the work, bills are piling up and it is difficult to make ends meet. Both Janice and Samuel are loving, caring parents to the children. Stress and occasional loud, dramatic arguments between them are also a challenge.

One Saturday night the children are playing and watching a wrestling show in the living room. Janice is in the kitchen cooking and the children are not in her line of vision. Samuel is at work. Kyle and Reena practice a risky move. They slam one another, bump into the coffee table, and three year old Izzy suddenly flies across the room and hits the wall in time for a framed picture to fall on his head. Izzy screams in terror and Kyle and Reena are also shocked, unsure if they are also injured or just shaken from their own practice (but playful) body slamming and the toddler’s bleeding and crying. Izzy will need medical care and Janice does not take public transit very often or drive. Janice is beside herself with fear and angry and scared for the older two as well. An ambulance would certainly involve the police. Urgent Care is closer and cheaper if someone could help.

In the status quo environment, the state would investigate Janice and Samuel and likely remove Izzy, if not two or all three of the children. An abolitionist response does otherwise:

STEP 1: With a trusted community member or professional who understands disability justice and physical disabilities, Janice, Samuel and the two verbal children have discerned a plan for emergencies such as this (Janice is parenting solo and cannot physically respond to the situation). The children had the opportunity to provide their own input individually (without one another, and without their parents) as best practices recommend. There are up to four safe adults in the neighborhood to call when a medical (or other) emergency arises. Here, the adult who responds first can rush Izzy and the other two children to nearby Urgent Care immediately to be examined and treated. The Urgent Care staff, like Eliza the social worker, understand the harms of the family policing system and instead want to work with Janice and Samuel to manage the situation and ensure safety without calling the child abuse hotline.38

STEP 2: Following the medical treatment, either one of the safe adults, or a trusted professional who understands disability justice and physical disabilities, can help the whole family do a strengths and needs assessment to address the situation. Either way, at some point it may be good to bring in a trustworthy professional who can discuss improving Janice’s disability access.

Extra support may be needed for any of the following (not an exhaustive list):

Kaba and Ritchie note that while the state’s narrow, carceral version of safety “robs our communities of the conditions and nutrients that would allow true safety to grow,” the abolitionist vision of safety consists of “a set of resources, relationships, skills, and tools that can be developed, disseminated, and deployed to prevent, interrupt, and heal from harm.” Building and strengthening the resources, relationships, skills, and tools described in this paper and illustrated in each of the scenarios “requires us to overcome the fear of, and alienation from each other that the state has perpetuated. . . Ultimately, there will be no safety that we don’t make through collective care and the relationships it requires.” (Kaba and Ritchie)

In pursuit of justice for parents with disabilities and their children, family policing abolitionists consider principles, processes, and support mechanisms that empower individuals, families, and communities to autonomously identify and implement what is needed for safety. In the world without family policing that we envision, justice for parents with disabilities and their children first and foremost means power to exert lived experience expertise about one’s own situation, condition, and wellbeing. Justice means trust in the wisdom and autonomy of both parents and children to craft individualized, lasting solutions that address the root causes of any crises or issues that arise. As the hypotheticals presented in this paper illustrate, key disability justice principles include advance contingency planning and collaboration with trusted, culturally humble professionals who center disability justice and recognize the harms of the family policing system and insistence upon resourcing parents and families directly, as opposed to resourcing programs and systems that perpetuate surveillance and control instead of support. Ultimately, effective responses to challenges experienced by parents with disabilities and their children would equip families and youth with processes and tools that lay the groundwork for webs of mutual care within their own communities where other people are similarly invested in their safety and wellbeing.

Human rights norms and literature and a wealth of other best practices prove that resources, power, and solutions are not found outside of any family or community, but within. Family policing distracts from the reality that certain communities have been historically trusted to problem-solve for themselves and all families – including those with disabilities – are thoroughly worthy of the dignity to determine their future and reclaim safety for themselves.

Charisa Smith (she/her/hers) is a Professor of Law at City University of New York (CUNY) School of Law whose work is cited by federal and state courts, agencies, and advocates. She is passionate about carceral and family policing abolition, re-imagining beyond ableist racial capitalism, and investing in youth leadership and power. Smith has represented youth and adults in criminal and civil contexts, with international human rights and alternative dispute resolution (ADR) experience. She is a graduate of Yale Law School, Harvard & Radcliffe Colleges, and Wisconsin Law (LL.M), where she was a Hastie Fellow. Smith’s research addresses state overreach into the lives of marginalized families, the overcriminalization of youth, cybersafety, and sexual/gender-based harms among youth. A longtime Zen Buddhist, Smith fosters mindful lawyering and balance in legal education.

Smith, C. (2025). Reclaiming Safety for Children of Parents with Disabilities. upEND Movement. upendmovement.org/safety