Reflections on upEND’s 5th Birthday

June 19, 2025

June 19, 2025

By Josie Pickens

“We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes.” That lyric, from Ella’s Song by Sweet Honey in the Rock—written in honor of the legendary civil rights organizer Ella Baker—echoes in my mind as I reflect on upEND’s fifth birthday. Five years ago, around Juneteenth—a celebration of delayed but hard-won freedom—a small collective of insiders-turned-abolitionists planted the seeds of upEND. In the summer of 2020, they dared to imagine a future where families would no longer live under the fear of surveillance and separation. Since then, upEND has grown into a force, challenging the foundations of family policing. And though I wasn’t there at the very beginning, I carry the torch forward with reverence and urgency.

upEND was founded by people who had spent years working to reform the family policing system—often called “child welfare”—and who witnessed firsthand the systemic harm it perpetuates. But over time, through lived experience and deep listening to impacted families, they came to understand what many already knew: reform is not enough. The system’s very foundation is rooted in surveillance, control, and punishment, particularly of Black and Indigenous families.

upEND was created to dismantle pervasive myths about the family policing system and provide public education that centers impacted youth and parents. From the beginning, we’ve worked to shift public narratives: family policing does not help—it harms. It removes children from their homes for reasons rooted in poverty, racism, and ableism, and it breaks apart families under the guise of safety. As Ruth Wilson Gilmore reminds us, abolition is presence, not absence—it’s about creating systems of care that render harm and punishment obsolete.

In 2021, on the first anniversary of our founding, we published How We endUP: A Future Without Family Policing. This document provided a collective vision for ending the separation of children from their families and reimagining safety and care outside of systems of policing and punishment. It lays out specific strategies, values, and guiding principles that align with abolitionist thought and practice. But we knew from the beginning these ideas could not remain static.

Movements evolve. Understanding deepens. New conditions arise. New analysis will always be needed in our movements. Our team is now revisiting this document to incorporate lessons from the past several years, including feedback from partners, impacted families, youth advocates, and fellow organizers. In our commitment to remain students of the movement, we see this revision not as a correction but as a deepening—a recommitment to collective liberation, rooted in flexibility and imagination.

Here are some of the lessons we’re reflecting on now:

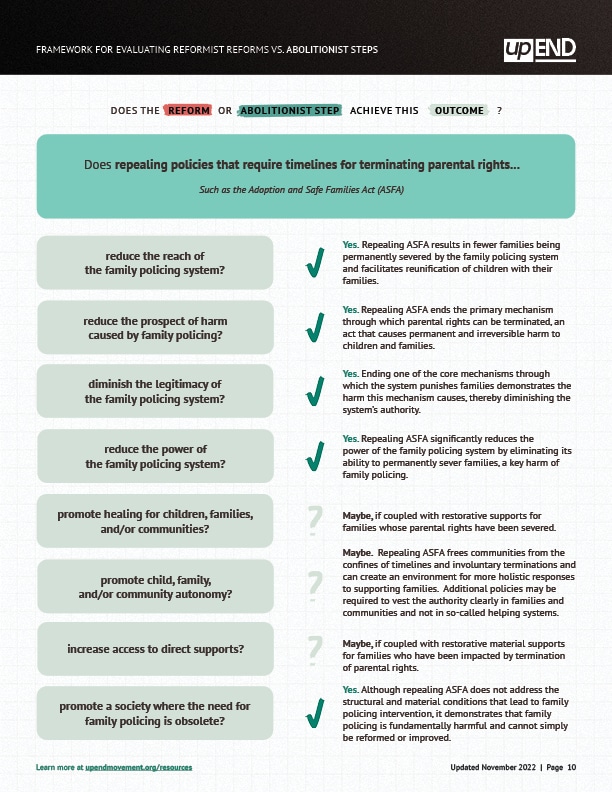

While our end goal is full abolition of all carceral systems, the reality is communities, children, youth, and parents are being harmed now. To that end, we are interested in intermediate steps that shrink the system’s power and reach, without giving more power or funding to harmful systems we want to end. Our abolitionist Framework Tool helps policy advocates and organizers assess whether policy changes move us toward or away from that vision. Intentional steps like defunding and reducing surveillance are not compromises—they are strategic acts of resistance (Gilmore, 2020).

Abolition does not exist in isolation. That’s why Season 2 of The upEND Podcast focused on building bridges with movements for international struggles against apartheid and settler colonialism, reproductive justice, prison abolition, immigrant justice , and queer and trans liberation. These cross-movement connections expand our vision and ground us in a future rooted in collective care and shared liberation.

Like many in this movement, we’ve long said: poverty is not neglect. And we’re clear—capitalism is the root of much of our communities’ suffering and the pipeline into the family policing system. But we want to push the conversation further. While it’s necessary to challenge the criminalization of poverty, we must also reject the binary that separates “deserving” parents—those who lose their children because of poverty—from “undeserving” ones accused of something else. That logic mirrors the harmful distinction between “violent” and “nonviolent” offenders—a binary that props up state punishment and chips away at our vision of real care and justice. When we say no child should be taken because of poverty, we also mean: no child should be taken by the state at all. We do not believe in state-sanctioned separation. Period. (Berlant, 2011).

Abolitionists are constantly asked: What about harm? We answer: the family policing system does not keep children safe; instead, community, care, and resources do. Our ongoing anthology, Reclaiming Safety, will explore non-carceral responses to harm, including substance use and sexual violence. We know that there is not one solution—there are many (Kaba, 2021).

From the beginning, upEND has been aligned with the reproductive justice framework: the right to have children, not have children, and to parent in safe, supported communities (Ross, 2017). As reproduction becomes increasingly criminalized, our work grows more urgent. We affirm that abolishing family policing is reproductive justice. We are working to deepen the connections between reproductive justice and family policing, including documenting the interlocking harms of both the family policing system and the adoption system—systems that have long targeted Black, Brown, and Indigenous families under the guise of care.

Our documentary, A Vision of Grace, created in partnership with Montrose Grace Place, uplifts the voices of youth navigating housing insecurity, many of whom have also endured family separation and the deep harm caused by the foster system. We have always understood the importance of centering the voices of youth impacted by the system as the source of where solutions should come from. Their stories remind us that those closest to the problem hold the keys to the solution. We continue to work with these youth to build a new generation of abolitionist organizers.

As we mark this milestone, we reflect not only on how far the movement to end family policing has come, but on the future we’re building—boldly and collectively—together. The fight against family policing is a cultural, ethical, and deeply emotional struggle. It requires us to tell new stories about what safety really means, to dream of a world we haven’t yet seen, and to commit ourselves daily to justice and joy. The work is far from over. But what gives me hope is the growing number of people—across communities, disciplines, and geographies—who are beginning to see what we see: that family policing is irredeemable, and that abolition is not only possible, it is the only way forward. This fifth anniversary is a renewal of our commitment to those who follow and support our work. We are building a future where families are not punished, but supported, where harm is met with healing, not handcuffs. And where children grow up surrounded by love, dignity, and care. We deeply believe that we can end up there, together.

Josie Pickens is a Black feminist educator, journalist, and community organizer and strategist. She currently serves as the Program Director of The upEND Movement.

Endnotes