Unlearning Punishment: Family Policing Abolition as Liberatory Praxis

“Abolition isn’t just about getting rid of buildings full of cages. It’s also about undoing the society we live in, because the PIC [prison industrial complex] both feeds on and maintains oppression and inequalities through punishment, violence, and controls millions of people.”[1]

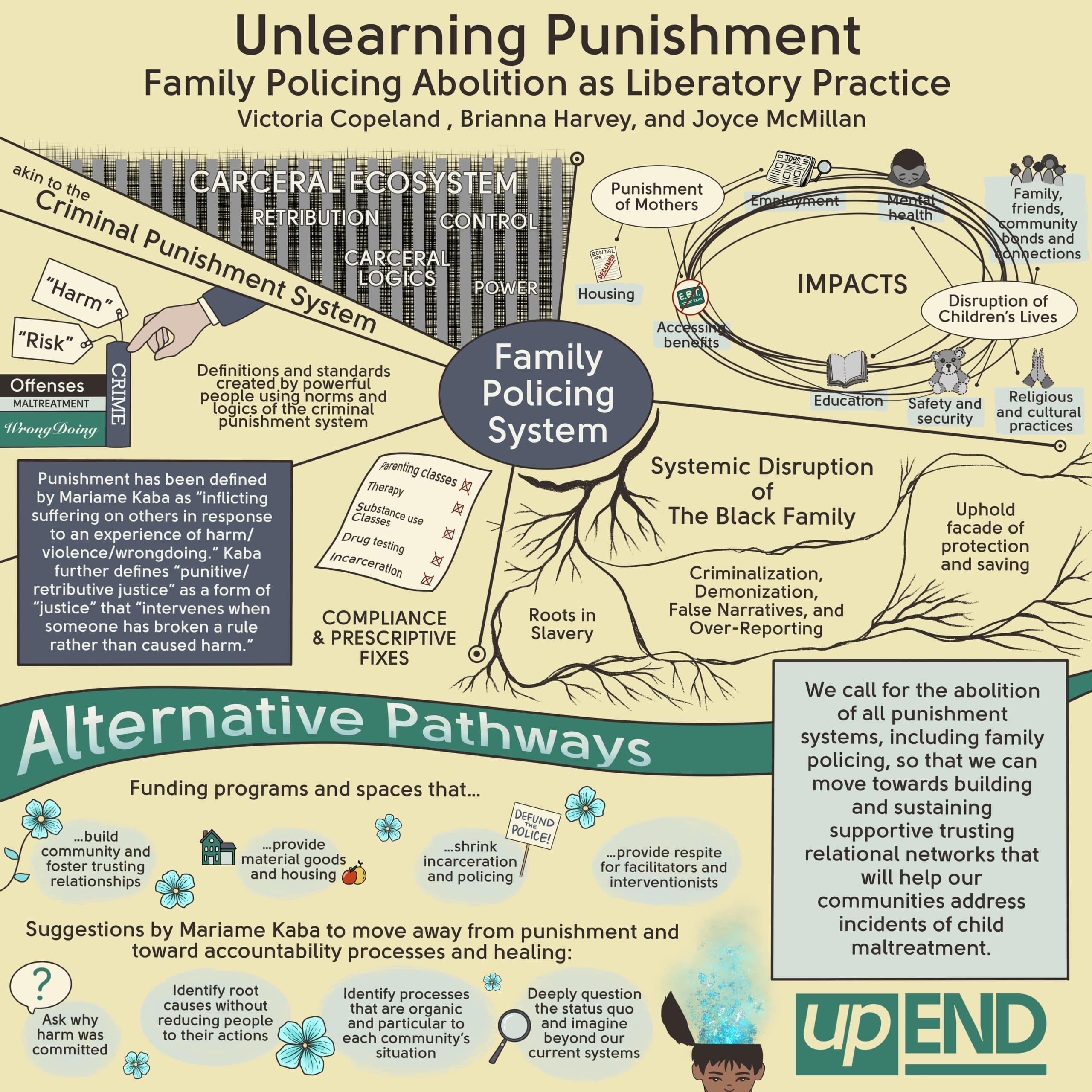

For years people have grappled with our society’s attachment to and reliance on the “criminal justice” or “criminal punishment” system.[2] Though much of these discussions have focused primarily on the institutions of prisons and practices of incarceration, organizers and activists have reiterated that policing and certain types of punitive justice-seeking mechanisms have proliferated through other social systems as well. Akin to the criminal punishment system, the “child welfare” or “family policing” system continues to be one of the most interconnected and embedded punishment systems within the carceral ecosystem, requiring the use of carceral logics and power to exert control over specific communities. Many advocates refer to child protective services agents as the family police because they serve similar police-like functions: investigating families and delivering state-sanctioned punishments to families and communities.

“Akin to the criminal punishment system, the “child welfare” or “family policing” system continues to be one of the most interconnected and embedded punishment systems within the carceral ecosystem”

Mariame Kaba defines punishment as “inflicting suffering on others in response to an experience of harm/violence/wrongdoing.”[3] Similar to this definition, Kaba further defines “punitive/retributive justice” as a form of justice that “intervenes when someone has broken a rule rather than caused harm,” adding that punitive justice is based on “punishments that are pre-determined” and “defined by the state” (cops, courts, prisons).[4] In this conceptualization of punishment and punitive justice, Kaba differentiates crime from harm stating that through a retributive justice framework, crime can be defined as “a violation of the law and the state.” Whereas within a transformative justice framework, crime is recognized as “socially constructed” with an understanding that everything that is criminalized “isn’t harmful, and all harm isn’t necessarily criminalized.”[5]

Much of what society has normalized as a “crime” has been created or fueled by racist, sexist, classist, ableist notions of what is considered safe, protective, helpful, or conversely risky and dangerous. As others have explained, our society has taken an orientation towards punishment, which continues cycles of violence that depend on carceral institutions for “remedies” rather than learning from and about non-punitive forms of accountability. Within a retributive justice framework, justice requires “the state to determine blame and impose pain (punishment).”[6] Thus retribution has included incarceration, fees, fines, and sometimes death for those involved in the criminal punishment system. For survivors or others who have experienced harm, seeking help from a criminal punishment system can lead to collateral forms of policing even though they did not “commit a crime.”[7]

Within the family policing system, we see similar instances of pre-determined punishment that are attached to various “crimes,” “offenses,” or wrongdoings. These crimes and wrongdoings are influenced by definitions of maltreatment that were created by the state which decided what should be considered “harm” or “risk.” These standards have been undoubtedly influenced by the same norms and logics as the criminal punishment system, placing largely poor Black and Indigenous families under the gaze and subsequent control of the state.

Punishment in the Family Policing System

Historicizing Slavery and Family Separation as Punishment

To fully understand the role of the family policing system and its systemic destruction of Black families we must acknowledge its roots within the institution of slavery. W. E. B. Du Bois posits, “One cannot study the Negro in freedom and come to general conclusions about his destiny without knowing his history in slavery.”[8] Similarly, we cannot begin to conceptualize the issues facing Black children in the current family policing system without understanding the historical connection to American slavery. If we do not draw parallels between the current system of control, punishment, and policing exacted over Black families in the name of “child protection” we are being irreverent and dismissing the violent destruction of Black familyhood and will be more likely to continue to uphold policies and practices which perpetuate further systemic oppression.

Ta-Nehisi Coates explains that the parting of Black families was “a kind of murder.” He adds “here we find the roots of American wealth and democracy – in the for-profit destruction of the most important asset available to any people, the family. The destruction was not incidental to America’s rise; it facilitated that rise.”[9] Here, Coates states that the destruction of Black familial bonds was essential for the building up of America’s wealth and was highly profitable. The means of separating families was essential to the foundations of our country, as it was a means to keep slaves “in line,” spread the production of capital, and control future reproduction of capital. Similarly, a quote from Peggy Cooper Davis reads “Slavery began, of course, with family separation, as men, women, and children were purchased or kidnapped from families and communities and transported among strangers to America and slavery.”[10] Here Davis points to the time of departure from Africa as the beginning of family separation, a process that was necessary to proliferate the global order with a violent exchange of human capital.

Under the legal and social construction of chattel slavery, Black children were deemed a commodity or property, something that could be bought or sold at any time if desired by the slave owner. The designation of Black bodies as a commodity stripped parents of their power and reinforced the idea of forced “parental helplessness” in which Black parents were robbed of their autonomy over the personhood of themselves and their children. During enslavement, Black parents were largely unable to control when or if their children would be removed from their care and sold to other slave owners. Further, Black parents were not considered human, rendering them unable to be considered a family by law. Thus, Black families had no means for protection from this violence. The cruel separation of families during slavery ensured that White slave owners could control and dominate capital, labor, and Black family reproduction. Further, they used family separation often as punishment for any disruptions slaves would cause on the plantation, or for disclosing plans of liberation.[11] One narrative recounts a story of a young enslaved mother whose “children had ‘all been sold away’ from her; that she had been threatened with sale herself ‘on the first insult’.”[12] In the narrative, the woman Cordelia said “‘I was not at liberty to make my grief known to a single white soul [regarding the selling of her children]. I wept and couldn’t help it’, but remembering that she was liable ‘on the first insult’ to be sold herself.”[13] It is important to note that enslavement and the family separation that accompanied it completely disregarded the fact that Black people were capable of feeling emotions or emotional connections to their children. As told by Cordelia, owners also often forbade the disclosure of these emotional bonds or behaviors of grief that were a consequence of family separation. In James Watkins recollection of family separation during slavery he recalls a time in which his owner refused to let him see off his relatives that were being sold to a different slave owner. He states, “I had to intercede with Mr. Ensor [his slave owner] for a length of time before he would consent to let me go on such an errand. At last, after ridiculing the idea of black people having any feelings, he consented.”[14]

Punishment in the Afterlife of Slavery

The current and normalized notions of who is considered a threat and under what circumstances cannot be separated from the histories of family separation within the U.S. context and beyond. Through the transatlantic slave trade, slavery began as one of the first institutionalized forms of family separation for Black children and families, this legacy of family disruption and destruction has continued through the family policing system and its attachment to retributive forms of justice seeking.[15] Under the present family policing system, the state has continued its attempts to exert control over parental autonomy by surveilling, monitoring, and removing Black children from their homes due to alleged cases of maltreatment.[16] As was recollected by James Watkins’ narrative, the family policing system does not often consider the emotional, psychological, and physical toll that separation or family policing system involvement has on Black families — instead weighing the child’s “safety” as most paramount regardless of the disastrous impact. Mothers continue to report that they experience worsened physical ailments, psychological distress, and emotional trauma for years after an experience with the family policing system. Children are often moved around, experience school disruptions, and can be pushed into other carceral systems.

In the family policing system, there are several forms of conduct or behavior that are considered wrongdoings or crimes by law. Further, there are discretionary and more abstract “behaviors” that have also been criminalized. For example, parental refusal of services, parental substance use, housing precarity, hygienic matters, mental and physical health issues, and types of employment have been criminalized by the system and have led to families becoming involved in the system. Moreover, although states vary in their inclusionary criteria for felony or misdemeanor charges for child maltreatment, most states will charge individuals for failure to report child abuse and neglect, assault, unlawful restraint, endangering the welfare of children, failure to protect the child form a case of serious malnutrition, “grossly negligent omission in the care of the child,” and various other “offenses.”[17] To make retributive justice work within the system, mandated reporters have been used to filter in those who might be committing offenses are wrongdoings. Mandated reporters are bound by provisions of the Child Abuse Prevention Treatment Act (CAPTA) and obligated to report families “suspected” of neglect and/or emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, or even a child being exposed to family violence. For example, in New York it is a misdemeanor for failure to report suspicions of family struggle, because struggles within a family are seen as some type of violation by the family policing system. Yet, these struggles are usually related to a lack of resources. This is not to say that real harm and violence does not occur within families, but rather it is important to be attentive to how punishment has been defined by the state and how the state poses appropriate retribution for the “offense.”

It is important to reiterate that the large majority of families continue to be involved in the family policing system for “neglect” more than any other type of maltreatment, yet this remains one of the most discretionary standards created by the state and policymakers.[18] Neglect in itself is embedded within assumptions about poverty and the criminalization of poor people. Further it is often used as a catalyst to supply families with “needed” preventative services that keep families under the eye of the broader system.[19] Neglect, or even “refusal of services,” being considered a criminal offense implicates parents in a highly personal way— holding certain parenting practices, housing environments, and access to resources as harmful while ignoring the harms of state violence and organized abandonment. When families face punishment through charges or investigations by the family policing system, they are expected to behave a certain way, follow certain guidelines, and adhere to a prescriptive retributive fix set out by the state that includes parenting classes, therapy, substance use classes, drug testing, and sometimes incarceration. Kaba states in her definition of punishment that the system inflicts suffering for what the state defines as a crime or wrongdoing, many times without addressing root issues of harm or changing the circumstances that have forced families into poverty. As a mother who has been impacted by the system, one of the authors of this paper, Joyce McMillan, believes it is absurd that child protective service agencies across the United States claim to fear for the safety of children when “safety” has never been the leading cause of investigations or family separations. Punishment and state sanctioned forms of retributive justice have impacted children, parents, and communities for generations.

Punishment Requires False Narratives and Impossible Standards

For the family policing system to uphold its facade as a “protection” system, it criminalizes and/or demonizes certain individuals. This often results in the criminalization and subsequent punishment of poor Black families, especially Black mothers. False narratives have always been an integral reason for the overreporting of Black parents and their subsequent involvement in the family policing system, and Black families are judged and punished for conduct or practices that other parents would not be investigated for. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a decrease in reporting calls to CPS, yet the family policing system created and reinforced narratives about Black parenting to alarm people and increase reporting from community and family members. The system pushed harmful and false narratives without any concern for the negative and traumatic experiences Black families have historically encountered during these family entrapments. As a parent impacted by the family policing system and someone who also works with other families impacted, Joyce knew this messaging was a stunt to keep pressure and surveillance on Black communities. She knew this was a desperate cry by the family policing system to keep the supply of children flowing into state custody and control. This type of marketing encourages people to weaponize CPS against families, and incites anonymous reporting, which is one of the components the system needs and regularly uses to continue its supply of children who are stolen from their homes and from loving parents or caregivers.

While the family policing system used false narratives to popularize the idea that Black parents might harm their children during the pandemic, many Black mothers have discussed how the system has caused them direct harm. Their lives have been impacted by the criminalization of their circumstances or their behaviors, which have been surveilled and scrutinized by the state and its actors for years. The system has historically inflicted suffering onto Black mothers, rationalizing this harm by convincing society that Black mothers have caused harm to their children, or might cause harm in the future. The system has used these false narratives to convince society that they are in the business of saving rather than harming. Black mothers have also complained that the system convinces their own families, including their children, that they are harmful and do not deserve to have parental rights. Through these narratives, the family policing system has punished mothers by taking their children away or forcing them into services, sometimes both. Even if the services are “voluntary,” mothers are punished if they refuse to take part in the services or refuse to otherwise “comply” with CPS workers requirements.[20] Subsequent punishment comes in the form of extended time within the family policing system, time in the criminal punishment system, or surveillance through multiple institutions.[21]

These tactics are not new but show the same strings of power that came from segregation, racist policies, policing, and criminalization of Black mothers from previous eras. These punishment practices have severe and sometimes long-lasting consequences. In New York, even when a report is not found to be credible, the record of the report against a family is kept on an internal list with a local CPS office for 10 years. Over the years a “founded” case of maltreatment in New York would remain on a list until the youngest child in the house at the time of the investigation turns the age of 28.[22] Punishment of mothers impacts their ability to attain or retain housing, ability to access benefits through social service agencies, ability to get future jobs due to criminal records, ability to move in the world “unmarked” and the ability to take care of future generations of family.

Although we focus on Black mothers here, we would be remiss to say that Black fathers are not also significantly harmed by the family policing system and broader carceral ecosystem. Black fathers historically have been rendered invisible by policies such as Aid for Families with Dependent Children, despite data showing that Black fathers remain engaged with their children.[23] Further, the family policing system is wantonly inept when it comes to engaging fathers and paternal relatives. Racist tropes and narratives of the dead-beat dad and angry Black man, combined with archaic beliefs that a father’s sole responsibility to his family is financial with little impact on children’s social and emotional outcomes only emboldens family trauma and terror at the hands of the state.

Collateral Punishment: How Family Policing Simultaneously Harms Children

Another egregious example of the ways the family policing system punishes families is through the impact it has on children that become entrapped within the system. When a child is removed from their home for “suspected maltreatment,” they become simultaneously punished and experience significant disruptions in every aspect of their lives from their education, religious and cultural practices, and connections to their family, friends, and local community. Schools often fail to understand the significant loss and trauma experienced by foster youth due to their removal from the home and instead disproportionately criminalizes their behavior through exclusionary discipline practices. Within Los Angeles County schools, which have the largest amount of foster youth enrolled in their K-12 education system, foster youth students are suspended and expelled at higher rates than both their foster youth and non-foster youth peers of other races.[24] This is further complicated by race and gender as Black male foster youth disproportionately experience this form of exclusionary discipline and punishment within schools.[25]

The family policing system also inflicts punishment on children through instability. At home, children can maintain a sense of security and safety through their bonds with their family and their neighborhood community. When children are taken from their homes and put into placement, their experiences with instability begin or worsen. Youth in the system experience multiple placement and school changes which have a negative impact on their educational trajectory, mental health, and overall well-being.[26] Children are shuffled between foster homes, congregate placements, and other forms of “care” because these placements are often touted as safer and more stable placements compared to a youth remaining with their family of origin. However, we see that children have continued to be harmed in out-of-home placements that claim to be “protective.”[27]

The family policing system functions as an oppressive system that uses punishment mechanisms to target and destroy Black families. It does this by utilizing false narratives to justify the destruction — breaking bonds not only between parents and their children but between the children and their grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and siblings once they enter foster care. The disruption of children’s familial bonds is rarely, if ever, considered when children are removed from their homes. The loss of safety, security, and autonomy causes many children to shift their behaviors, and causes changes in their mental health such as experiences of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and ADHD.[28] Further, Black and brown children are often not given necessary mental health support in placement and are the most likely to be over prescribed psychotropic medications. These medications can further exacerbate feelings of fear, isolation, and grief. Many children also begin to internalize and often blame themselves for being removed from their home.[29] This internalization can make youth less likely to be open about other incidents of harm they have experienced for fear of being removed or put into placement again even after their return to the home.

“It is clear that families are safer when their children are at home and not being policed by a system that looks for frivolous reasons to intrude into families’ lives, wreaking havoc and threatening separation.”

It is clear that families are safer when their children are at home and not being policed by a system that looks for frivolous reasons to intrude into families’ lives, wreaking havoc and threatening separation. Advocates have been fighting for decades to have resources used in the homes of children where families face financial hardships because we are aware of the extreme harms caused to the entire family by CPS, including the child they claim to protect.

But instead of supporting families, the government has framed funding as a resource to provide for out of home placements, energizing the breaking of families and bolstering the growth of industries that partake in the harm.

Rejecting Punishment Regimes that Harm our Communities

“Transformative justice takes as a starting point the idea that what happens in our interpersonal relationships is mirrored and reinforced by the larger systems. It’s asking us to respond in ways that don’t rely on the state or social services necessarily if people don’t want it. It is focusing on things that we have to cultivate so that we can prevent future harm.”[30]

In “Against Punishment” Mariame Kaba writes that “violations” or circumstances in which people are harmed offer “opportunities for accountability at individual, community, and societal levels.”[31] Through transformative justice, communities can engage in “naming and transforming violence into growth and repair” which requires collaborative work between survivors, individuals who caused harm, and community. These collaborative processes can enable individuals and communities to “transform conditions that led to the harm(s) in the first place.”[32]

The current family policing system does not allow for pathways toward transformative justice because it is heavily reliant on modes of punitive justice. This reliance on retribution entrenched in punishment cyclically harms those who may have experienced harm. In its efforts to “protect” children at all costs, the family policing system has deputized workers and community members and created policies that reprimand those who do not wish to partake in investigatory or surveillance mechanisms. As stated previously, the punitive consequences for not reporting have caused teachers and other workers to become deputized to report families, encouraging a report with no provision, expectation, or intent to support families. It is harmful for a family to need resources while being afraid to share that they are in need with professionals who claim to “help.” Within this dynamic, professionals are consistently gatekeepers of both knowledge and access to resources that could mitigate a family’s struggle. This paradox has been exacerbated by the requirement for workers to report, which has diminished the ability for workers to intervene in a way that provides resources. Instead, workers have resorted to calling in families to the child protection hotline so that they can be investigated. This circumstance provides a snapshot into the practices that capture families for the purpose of punishing and controlling them. As Kaba highlights, the criminal punishment system often states that it is “fighting for victims” but fails to include victims’ real interests or needs. State vengeance does not equate to accountability, healing, or consequences that are survivor created or survivor centered. Although family separation is argued as a consequence to “child maltreatment,” it is enacted through state violence and surveillance, often in conjunction with several other forms of punishment that are frequently far removed from the interests of those who are being harmed. Additionally, in its efforts to punish those who have caused harm, the system also punishes those who have simultaneously experienced harm through poverty, interpersonal violence, or intergenerational trauma.

To move forward it is essential for us to imagine alternate spaces and processes that do not require the family policing system or punishment systems. Similar to Kaba, as abolitionists we are concerned primarily with “relationships” and “how we address harm,” acknowledging that state violence that is extended through punishment practices fails to adequately address child maltreatment and instead creates a cycle of generational punishment.[33] In an interview between adrienne maree brown, Autumn Brown, and Mariame Kaba, Kaba differentiates punishment from consequences stating that punishment and patriarchy necessitate one another, with punishment inflicting cruelty or suffering in ways that make it so people are unable to “make a life livable.”[34] Conversely, consequences enable victims/survivors to create or maintain boundaries, reducing power from those who have caused harm, and adjusting circumstances that might allow for those who committed harm to seek accountability. Consequences are central to Kaba’s vision of transformative justice, and a pathway to healing for those who have experienced and/or caused harm.

Alternate ways of responding to interpersonal harm encourage active responses to repair relationships rather than relying on passive “justice-seeking” through punishment and punitive systems. Dismantling systems of oppression and structures such as the family policing system would give us the opportunity to redirect resources and funding directly to communities most in need. We must fund programs and spaces that help build community, foster trusting relationships, provide material goods and housing, shrink incarceration and policing, provide respite for facilitators and interventionists, and address other issues within our communities rather than continuing to separate children and families. Kaba advocates for survivors and victims to get support that does not rely on prosecution such as paid counseling, paid trips that would allow for healing processes, and many other imaginative processes that would allow for us to transform our responses to harm.[35] Further, she provides several suggestions that could help us move away from punishment and toward accountability processes that might lead to healing including asking why harm was committed, identifying root causes without reducing people to their actions, deeply questioning the status quo and imagining beyond our current systems, securing safety and healing, identifying processes that are organic and particular to each community’s situation, and thinking through what community needs to make a process accountable.

We call for the abolition of all punishment systems, including family policing, so that we can move towards building and sustaining supportive trusting relational networks that will help our communities address incidents of child maltreatment. We call for the shrinking of punishment systems, whether that may be through removing mandated reporting requirements, requiring informed consents and legal support for those involved within the system, and removing higher education incentivization schemes that require social workers to “pay their debts” by working for the family policing system. We believe that there is work to be done, but that the family policing system makes these pathways to transformative justice both inaccessible and unfeasible. It is difficult to dedicate our lives to addressing harm in a non-punitive way when the family policing system is constantly hurting our communities. However, together, we can continue creating pathways that move away from punishment and instead collaboratively learn how to find or shape spaces for healing, mutual aid, and care.

By Victoria Copeland, Brianna Harvey, Joyce McMillan[36]