Regulating Families: How the Family Policing System Deconstructs Black, Indigenous and Latinx Families and Upholds White Family Supremacy

“We are told that the police are the bringers of justice. They are here to help maintain social order so that no one should be subjected to abuse. The neutral enforcement of the law sets us all free. This understanding of policing, however, is largely mythical. American police function, despite whatever good intentions they have, as a tool for managing deeply entrenched inequalities in a way that systematically produces injustices for the poor, socially marginal, and nonwhite.”

– Alex Vitale in The End of Policing

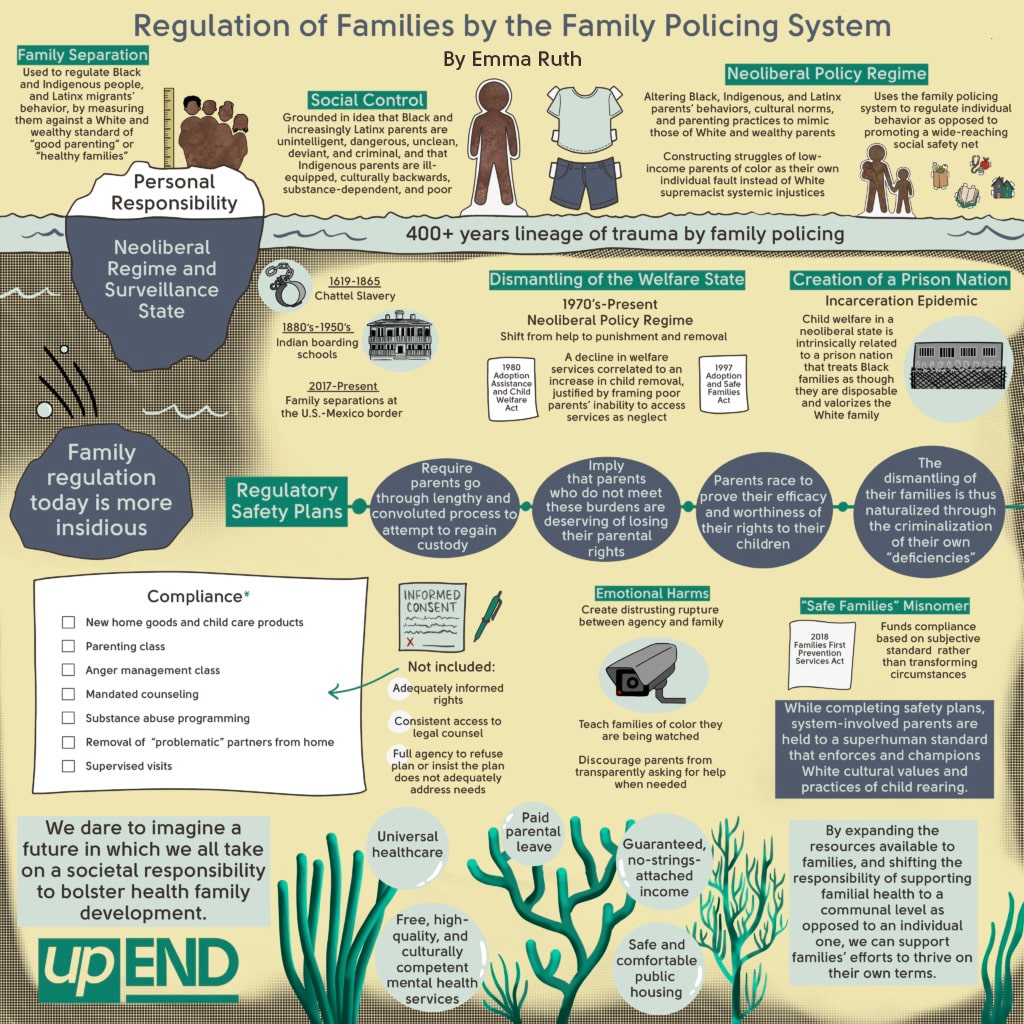

At the upEND Movement, we examine how policing manifests in the child welfare, or family policing, system. The family policing system “polices” in three main ways: surveillance, regulation, and punishment. These practices predate the founding of the formalized family policing system. In fact, the practice of White elites surveilling Black, Indigenous, and Latinx parents, using the threat of child seizure to incentivize their compliance, and removing their children predates the founding of the United States.[1] The separation of families has historically been used as a way to regulate Black people, Indigenous people, and Latinx migrants’ behavior, upholding the supremacy of the White family by measuring Black, Indigenous, and increasingly Latinx families against a White and wealthy standard of “good parenting” or “healthy families.”

Present-day child seizure by the family policing system has much in common with child seizure that took place during human chattel slavery, at Indian boarding schools, and presently at the United States-Mexico border. When child seizure originated with chattel slavery, the practice was explicitly justified with anti-Black racial logic (e.g., Black people were deemed subhuman and treated as property, and thus they did not have human rights like custody of their children). As we’ve evolved to reach an era that the White dominant culture falsely deems “post-racial” or “color blind”[2] due to conformist advances of people of color, the racism of the family policing system’s child seizure policies is no longer explicit, it has become more discreet. The way that custody is now policed is much more insidious and framed to blame poor parents for their own poverty and Black, Indigenous, and Latinx parents for their own nonconformity with perceived White cultural parenting norms.

Today, regulation is the practice of altering Black, Indigenous, and increasingly Latinx parents’ behavior, cultural norms, and parenting practices to mimic those of White and wealthy parents. This is a practice of social control, grounded in the idea that Black and increasingly Latinx parents are unintelligent, dangerous, unclean, deviant, and criminal, and that Indigenous parents are ill-equipped, culturally backwards, substance-dependent, and poor. Throughout the U.S. history of family separation and regulation, this practice has been reinforced through the strategic employment of “personal responsibility” rhetoric that construes an individuals’ “fitness” to be a parent as a matter entirely within their control, unrelated to external factors like the neoliberal regimes or surveillance states that those parents live in. This forces parents to internalize dominant messaging about what is an acceptable job, communication style, or partner, and results in compliance with the family policing system’s demands. When examining the contemporary family policing system, it is essential to contextualize its current practices within this 400+ year lineage and recognize how this history still manifests in the family policing system today.

Chattel Slavery 1619 – 1865[3]

The U.S. legacy of a White ruling class removing children from low-income parents of color and separating marginalized families began with the practice of human chattel slavery, which reached what is now known as the United States in 1619. Viewed as property, enslaved Africans were not afforded the same rights to family unity as White enslavers. This reality, paired with racial demographics of the family policing system presently,[4] indicate that both then and now, Black families experienced the damage of child removal and family separation at disproportionate rates.

As a result of the conditions of their bondage, enslaved children lived in constant fear of removal from their families; their anxiety was evidence of the precariousness of the Black family, and the longstanding trauma that Black families in the United States have endured. Enslaved parents felt anxiety about family separation, which they passed onto their enslaved children – this anxiety continued intergenerationally and persists to this day.[5] Families that come in contact with the family policing system experience a new iteration of the trauma that previous generations experienced – the stability of their family is uprooted, and family members are forced to fight for their family’s unity.

“In 2020, Black children made up 25% of youth in foster care, despite comprising only 15% of the national child population. In response to this precarity, Black parents are often forced to comply with dominant White systems.”

Then and now, Black families are precarious, as they are disproportionately likely to be intervened upon by the family policing system. In 2020, Black children made up 25 percent of youth in foster care, despite comprising only 15 percent of the national child population.[6] In response to this precarity, Black parents are often forced to comply with dominant White systems. The family policing system requires parents go through lengthy and convoluted processes to attempt to regain custody. While enslaved parents had to endure their bondage, strategically utilizing compliance and “good behavior” to avoid being sold and separated from their children, (disproportionately Black) parents involved with the family policing system have to prove the legitimacy of their right to custody by demonstrating their “fitness” as parents by jumping through the hoops imposed by their service plan. Black parents involved in White supremacist systems from 1619 to present have had their behavior regulated and have had to demonstrate their compliance with these systems to preserve the unity of their families.

Native American Youth: Indian Boarding Schools and Child Removal 1880s – 1950s

The removal of Native American youth from the inception of Indian boarding schools in the 1880s through their decline in the 1950s was a tool to dismantle Native American cultural values, religions, and ways of living and institute White cultural standards. The title of Captain Richard H. Pratt’s now infamous 1892 speech “Kill the Indian, Save the Man”[7] indicated that instead of supporting a physical genocide of “men,” he advocated for a cultural genocide of “Indians,” regulating Indigenous people’s identities by requiring them to embrace White behaviors and cultural norms. Famous photos like these show the impact of this cultural genocide, and the way it imposed strict White expectations of “normalcy” on Native American youth by forcing children into garments that were common of Whites and westerners, cutting boys’ long hair off, and prohibiting the practice of Indigenous religions or languages.

In addition to teaching Native American children White settler-colonizer culture, Indian boarding schools also denied parents the opportunity to pass their own cultural values onto their children. These schools constructed White supremacist institutions and their staff as superior caretakers to the children’s own Indigenous families. Much like family separations throughout enslavement, Indian boarding schools were undeniably traumatic for parents and children alike. Recent retrospectives[8] indicate that there was rampant physical, mental, and sexual violence throughout these facilities. By denying parents the opportunity to socialize their own children and exposing children to intensive violence, Indian boarding schools caused intergenerational trauma,[9] similar to that experienced by people who were enslaved.[10]

After terminating tribal recognition for 109 tribes and transferring jurisdiction of Indian affairs from federal to state governments around the 1950s Native Americans became more dependent on welfare. Native Americans’ financial insecurity was then used to justify the removal of Native American children by the family policing system at alarming and disproportionate rates. In response to this child removal crisis, the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was passed in 1978. This act was Congress’s first acknowledgment that the impacts of the Indian Adoption Project – and the longer history of displacing and dismantling families – was detrimental, but this acknowledgment did not bring resolution. Indigenous children are still removed from their homes at disproportionate rates, and the question of saviors versus captors was raised again in a 2013 Supreme Court case. In Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl, a White family adopted a multi-racial baby who had Cherokee heritage, despite the objections of her Cherokee father. Scholar Alyosha Goldstein argues that “Adoptive Couple, and the protracted legal and jurisdictional struggles in its wake, has much to do with the reassertion of White heteronormative rights to possess and to deny culpability for the ongoing consequences of colonization and multiple forms of racial violence in the present moment.”[11] Much of the public – and the Supreme Court’s ultimate decision – were in support of the White adoptive parents. This recent example demonstrates that this understanding of White adoptive parents as generous baby-savers, as opposed to actors in perpetuating a larger cultural genocide, persists today.

Neoliberal Policy History 1970s – 1997

From chattel slavery to the present day, the White U.S. government has systemically dismantled Black families, rendering them disposable and undeserving of resources. A series of policy decisions between 1970 and 1997 and recent data regarding the impacts of said policies demonstrate how a neoliberal policy regime crafted by the federal government built up the United States prison nation through crime acts and hindered social service access for low-income people of color through child welfare acts. These policies destabilized Black families, incarcerating Black people at disproportionate rates and constructing low-income Black people as unfit parents, resulting in the removal of Black children and their placement in the care of White foster parents. Particularly, these policies reflected a neoliberal shift away from social service provision towards a system that emphasized “personal responsibility.” Instead of identifying White supremacist systemic injustices as legitimate barriers to effective parenting, this neoliberal policy regime criminalized Black people and constructed the struggles of low-income parents of color as their own individual fault, making the idea that Black people are inherently inferior parents hegemonic and bolstering support for programs that altered Black parents’ parenting.

Understanding Racialized Crime Acts and the Prison Nation

Three acts from the 1970s through the 1990s characterized the racially biased and increasingly punitive neoliberal approach to crime, which disproportionately impacted Black people. Though neoliberalism is a wide-reaching system with vast impacts, its effects on the U.S. prison nation manifested through the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, and the 1994 Violent Crime Control Act. As a result, this era saw rapid growth in which offenses were criminalized, how severely they were criminalized, and the population of prisons. The rhetoric of the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act made the racialized dimension of neoliberalism especially salient by inordinately punishing crack offenses (which were associated with Black drug users) to cocaine offenses at a rate of 100:1.[12] This overemphasis on the impacts of crack cocaine as opposed to other formulations was reflected in the national panic over “crack babies,”[13] children who were supposedly born victims of their Black mothers’ “immoral” drug use. Black communities faced hyper-criminalization both socially and physically.

Amongst other impacts, these policies contributed to an unprecedented proliferation of incarceration rates as the U.S. prison population reached the largest in the world.[14] Eric Schlosser described this, setting the scene in his 1998 The Prison-Industrial Complex – “In the mid-1970s the rate [of incarceration] began to climb, doubling in the 1980s and then again in the 1990s.”[15] Schlosser goes on to highlight that Black men were disproportionately incarcerated throughout this period.[16] The neoliberal crime control policy regime stemming from the 1970s created an incarceration epidemic[17] that continues to plague Black Americans to this day,[18] both through the systemic removal (via incarceration) of Black parents from their families and through the ideological construction of Black people as criminals. This mental and physical criminalization of Black people laid the groundwork that justifies the regulatory practices in the contemporary family policing system.

Examining the Concurrent Decline of the Welfare State

Simultaneously, this neoliberal policy regime altered child welfare policies, shifting the focus from a “helping” system to a punishment and family separation system, which also disproportionately impacted Black families. More aligned with the “helping” approach, the 1980 Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act allocated $3.3 billion to a federal matching fund for state social services, vastly enhancing the capacity of the child welfare system to aid families in poverty. The 1980 act worked to remedy the troubling history of federal subsidies given to states with high foster care populations, which incentivized child removal without any good faith family preservation efforts.[19] Instead this 1980 bill bolstered and encouraged family reunification services. The Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act reflected a more liberal and less regulatory welfare approach: supporting families who struggle to get by in a system that deems wealth a prerequisite to successful parenting. But this open-handed child welfare program did not withstand Reaganomics. Reagan’s presidency and his undermining of the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act represented the end of the “helping” approach to child welfare, curtailing a broad social service system that would have supported impoverished families, instead implying that it was parents’ own responsibility to achieve success regardless of the dearth of resources available to them.

The following 1997 Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) put into law a more punitive, removal-focused approach, eroding the 1980 focus on family reunification in favor of a response that punished “noncompliant” parents with the termination of their parental rights. ASFA required the termination of parental rights for any parent whose child spent 15 of the most recent 22 months in foster care. Given the Reagan and Clinton administrations’ gutting of welfare services, low-income families were without help and experiencing heightened poverty and income inequality.[20] As children were removed in response to parents’ inability to materially provide for their children, the window of opportunity for regaining custody narrowed. A decline in welfare services correlated to an increase in child removal, which was justified by framing impoverished parents’ inability to access social services as child neglect. As a result, parental rights are terminated and children are swiftly adopted by families who would not need to access welfare in the first place – predominantly White and wealthy people.[21] The ASFA put into policy the Reagan-era undercutting of child welfare, leading to the fragmentation of welfare-dependent families.

Concurrently, the aforementioned crime acts criminalized a wider array of offenses, accelerating rates of incarceration and lowering the threshold for deeming someone “criminal,” making narratives of Black deviance even more wide-reaching. The window for regaining custody of one’s child shrunk, as did access to social services[22] which can make regaining custody more feasible, such as food stamps, public housing, etc. These cutbacks made it less and less possible for parents of color to prove their parental capabilities to the state, which meant that complying with interventions from the start and conforming to efforts to regulate their parenthood became even more urgent. White and wealthy parents who did not need to adapt their behavior to prove their parental capabilities were able to adopt those children.

The Impacts of the Neoliberal Policy Regime: Regulating Black Families

In Shattered Bonds: The Color of Child Welfare, legal scholar Dorothy Roberts discusses the impacts of neoliberal ideology on Black parents, commenting on the tangible harms of the neoliberal “personal responsibility” ideology.[23] Roberts explains, “because the system perceives […] harm to children as parental rather than societal failures, state intervention to protect children is punitive in nature.”[24] She highlights that in order to rationalize a system that accelerates terminating parental rights, the state must blame inadequate parents instead of its own policy failures. As a result, government efforts to promote safe families culminate in using the family policing system to regulate individual parents’ behavior as opposed to promoting a wide-reaching social safety net. Through a series of stipulations like parenting classes, alterations to a family’s home, mandated therapies, and supervised parental visits, parents race to prove their efficacy and worthiness of their rights to their children. This implies that those parents who do not meet the incredible burden that the family policing system places on them are deserving of losing their parental rights and thus, the dismantling of their family is naturalized through the criminalization of their own “deficiencies.”

How Black Families’ Fragmentation Upholds White Families’ Supremacy

Shattered Bonds describes how White families are reinforced through systemic advantages and less discrimination. Black families are less likely to receive reunification services than White families, Black children are disproportionately represented in foster care, and children in foster care are inordinately likely to be incarcerated.[25] The relocation of Black children to White families upholds White supremacist stereotypes about White people’s superior parenting capabilities. This cycle perpetuates the neoliberal “personal responsibility” ideology by relocating those children born to parents who the state deems unfit to the homes of parents presumed to be more qualified, which in practice is White and wealthy parents. Through this practice of criminalization and separation, the state deems White people to be more proficient and more deserving parents. Practicing child welfare in a neoliberal state is intrinsically linked to a prison nation which treats Black families as though they are disposable and valorizes the White family.

Family Separations at the U.S./Mexico Border 2017 – Present

In July of 2017, when the Trump administration began separating children and parents at the U.S./Mexico border and instituting a “zero tolerance” policy on immigration, public discourse about what rights parents had to their children and what constituted a “good parent” erupted. Conservatives argued that those who crossed the U.S./Mexico border without documentation were criminals,[26] and that by acting “unlawfully” they endangered their children and forfeited their parental rights. By removing children from their parents’ custody and failing to provide any clear documentation that would ensure their smooth reunification, the Trump administration implied that Latinx migrant parents were unfit. In 2018, Trump defended his family separation policy, stating “if [migrants] feel there will be separation, they don’t come.”[27] In this statement, Trump patently acknowledges that he is using separation of undocumented immigrant families as a threat to regulate migrants’ behavior and discourage subversion of U.S. immigration policy. This goes hand-in-hand with racist messaging that painted Latinx migrants as criminal,[28] contrasting them against the White standard of “responsible” parents as law-abiding and neutral, not subversive, to the state.

In their poignant analysis of this practice and its resultant implications, Adela C. Licona and Eithne Luibhéid argued that:

The forced separation of migrant families at the border fits into the United States’ long history of treating enslaved families as property whose members can be sold away from one another; forcing Native American children into boarding schools designed to violently strip away their language, culture, identity, family and community ties; [and] immigration policies designed to prevent immigrants of color from settling and forming families (45-46).[29]

Licona and Luibhéid contextualize family separations at the U.S./Mexico border within this larger project of cultural genocide. By stripping children from marginalized backgrounds of access to their parents, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) also severs children’s connections to their cultural heritage, preventing the continued development of these distinct cultural identities within the U.S.

Later in 2018, Trump signed an order halting his policy of family separation[30] after widespread public outcry about ICE’s failure to adequately track detainees to make reunification of families possible. However, family separations persisted[31] due to a technicality through which children can be removed if parents are deemed “unfit to care for a child” by border patrol agents. As a result, some children languish in detention facilities with substandard qualities of living,[32] and others are placed with U.S. citizens and foster families,[33] reifying all the notions of saviorism and amplifying the public construction of migrant parents as “criminal.” Regardless of foster families’ benevolent public image, children placed in both foster families and detention facilities faced rampant physical and sexual abuse.[34] Fear of exposing children to these harms has become a feature of U.S. immigration policy, as separation and violence towards children is regarded as a threat to dissuade prospective migrants who are often moving to the United States to escape violence and instability that the United States caused in their countries of origin.[35] As a result, parents who brave the treacherous immigration journey with their families are then characterized as irresponsible and unloving parents for exposing their children to the risks of immigrating, overlooking the risk assessment that parents had to make when deciding whether to leave their children in the difficult circumstances where they were raised.

Regulation Today

Today, we see formalized practices of behavioral regulation continue in the family policing system. When family policing agents intervene in a family, their safety plan can include mandating that parents buy new home goods and child care products; attend parenting, anger management, and substance abuse programming; receive mandated counseling sessions; and remove partners that they deem “problematic” from the home.[36] For example, in states where bed-sharing is seen as child maltreatment, parents may be asked to buy their child their own bed or crib. Parents are “asked” to make these adjustments because these safety plans are supposedly voluntary. But when parents are threatened with the prospect of losing their children, they are understandably reluctant to refuse any part of the plan. Parents are not adequately informed about their rights, infrequently have access to legal counsel, and do not have full agency to refuse the plan or insist that the plan does not adequately address their needs.[37]

These regulatory requirements are harmful in myriad ways and rarely address the circumstances that led to a family’s involvement with the family policing system in the first place. The 2018 Families First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) is a clear example of this: its name is a misnomer suggesting that it supports prevention services, when in fact, it funds the aforementioned regulatory measures. If a parent is sharing a bed with their child because they cannot afford to buy another bed or crib, mandating that they buy this unaffordable item only exacerbates their financial insecurity. A preventative plan would have focused on preventing families from entering the position of financial scarcity in the first place. In this way, the safety plan does more to mandate a host of tasks that bring a family closer to appearing “compliant” with the subjective and biased standard that the family policing system imposes than it does to transform the circumstances that made the initial maltreatment possible in the first place.

Though there have been sporadic efforts throughout history to shift towards models of child welfare that prioritize family unity and instances of offering cash assistance to families,[38] these small advances often categorically excluded Black families and only benefited poor White families. The FFPSA, for example, included provisions that offer financial assistance to unrelated (often White) foster parents but not the (often Black) family members who parent youth relatives through next-of-kin placements. This prioritization of White families conveys the message that White families are less harmful and more redeemable than families of color, and more deserving of social and financial assistance.

The harms of regulatory safety plans are not only financial, but also emotional. When White family policing agents who are prone to misperceiving and villainizing people of color (especially Black people) ask that parents attend anger management courses or substance abuse treatment, they create a distrusting rupture between agency and family, teaching families of color that they are being watched, discouraging parents from transparently asking for help when needed,[39] and inconveniencing parents further. While completing safety plans, system-involved parents are held to a superhuman standard that enforces and champions White cultural values and practices of child rearing.

This celebration of White parenting conveys the notion that White parents are superior caregivers and simultaneously, these regulations often do not impact White families in the same strenuous ways. Caseworkers, counselors, and attorneys acknowledge that they hear White parents admit to using drugs at the same or higher rates[40] than their clients of color, but they are still less likely to be subjected to safety plans.[41] If we look at the 400+ year history of regulating parents of color and constructing them as deviants or criminals, we can see that this exceptional treatment of White parents reveals the true purpose of family regulation. Family regulation is not about solving the circumstances that may create child maltreatment but instead it is about controlling the behavior of Black, brown, and Indigenous families. Embedded into the fabric of U.S. culture, law, and practice is the notion that Black, brown, and Indigenous parents are inherently deviant and less skilled parents, that their children are victims of their deviance, and that they do not deserve equal access to the basic right to raise their own children.

Moving Beyond Regulation and Family Policing

At the upEND Movement, we dare to imagine a future in which we all take on a societal responsibility to bolster healthy family development. In this future, we appreciate the origins and strengths of different cultural approaches to childrearing instead of trying to force every family to conform to one vision of “success.” We transition away from viewing a child’s health as an individual parent’s responsibility and towards understanding that we are all responsible for creating a world in which children and parents can thrive. Accordingly, we do not blame individual parents’ shortcomings (or racialized groups’ supposed inadequacies) for children’s struggles, instead faulting the cultural and political failures that have fostered an environment that does not nurture families’ health.

To pursue this end, we have to rethink and recommit where we focus our efforts to strengthen families. Existing reforms focus on expanding the assortment of classes, programs, treatments, and mandates that system-impacted families are subjected to. We want to do away with “subjecting” anyone to anything, refusing to accept the idea that Black, Latinx, and Indigenous parents are “subjects.” Instead, we fight to see the end of the family policing system and to invest in ongoing efforts to shift towards a model of community child rearing and expanding the social safety net for families (without expanding the network of surveillance and regulation). This can include measures such as:

- Guaranteed, no-strings attached income

- Safe and comfortable public housing

- Free childcare

- Paid parental leave

- Free, high-quality, culturally competent, and anti-racist mental health services

- Universal healthcare

By expanding the resources available to families and shifting the responsibility of supporting familial health to a communal level as opposed to an individual one, we can support families’ efforts to thrive on their own terms.

By Emma Ruth