Upending The Racialized Family Ideal

April 11, 2024

April 11, 2024

by Katie Gibson

What is one of the most heavily regulated economic institutions in contemporary America? Arguably, the family.

It may seem counter-intuitive to refer to the family as an economic institution, in part because we tend to associate family with privacy and with spontaneous (and unpaid) care. While it is certainly the case that families can be sites of love and nurturance in which we voluntarily participate, they are also sites of care-work that are structured by ongoing and concerted policy interventions designed with a key economic goal: to maintain care as a private affair rather than a public good.

As Melinda Cooper illustrates in her analysis of the history of welfare policy in the U.S., the state has long created and enforced familial bonds in order to shift the costs of providing care away from public institutions and onto private households: “Just as the Freedmen’s Bureau created legal marriages ex nihilo without bothering to secure the consent of either partner, modern-day welfare law conjures family relationships into being as a way of enforcing the legal obligations of mutual dependence and support.” For instance, child support laws, which have been used to police Black men in particular, often in ways that damage relationships between Black mothers and fathers, are designed based on the premise that care for children is a private responsibility rather than a public project or social right.

So why does a country known for free-market individualism invest so many resources in regulating and policing families? Abolitionist activists and thinkers argue that it’s because the unpaid care-work we do in our homes, as well as underpaid domestic labor, is what makes our current economic system run. As M.E. O’Brien writes:

“Capitalism relies on a large number of people being able to show up for work each day, and for the workforce to be maintained from one generation to the next. Those people don’t just magically appear; they arrive at the workplace, having been raised and cared for by families. For every worker, someone had to gestate and give birth to them, care for them as infants, raise them as children, and teach them the skills to navigate the labor market and find a job.”

In the words of Ai-jen Poo, an organizer for the National Domestic Workers Alliance, care-work is “the work that makes all other work possible.” Feminist historian and domestic labor organizer Premilla Nadasen makes the case that capitalist profit from the unpaid or underpaid care-work of poor women and women of color is not a recent problem. It has been a throughline of American social policy: from chattel slavery to Reconstruction Era vagrancy laws that enforced underpaid domestic labor, from New Deal policies that excluded BIPOC families from receiving housing subsidies and welfare benefits, to neoliberal policies that force poor mothers to work in exchange for meager welfare benefits under the threat of family separation. The U.S. has long worked to maintain a class of “disposable” workers, not only through carceral policies that regulate communities and families but through social welfare policies as well.

As Dorothy Roberts’ work illustrates, the state doesn’t just regulate families by creating and enforcing familial obligations; it also does so by disrupting the bonds people choose and shifting parental rights and obligations to foster and adoptive parents. States systematically surveil, pathologize, and incarcerate poor families through “child welfare” policies like CAPTA, which established a system of mandated reporting and investigations premised on the idea that child maltreatment was a symptom of parental pathology. From its inception, CAPTA worked to minimize the public costs of care and protect the financial interests of exploitative employers instead of protecting American workers and their children. The advocates and policymakers involved made a concerted effort to draw attention away from the economic causes of child neglect, such as parents’ employment in a labor market that reaps immense profits by paying less than a living wage and refusing to provide parental leave or subsidized childcare.

Family and child welfare policies shore up wealth and power for some and ensure the exploitation and oppression of others by rewarding those who uphold the American “family ideal” and policing, punishing, and profiting from those who don’t meet it. The “family ideal” is not just a household of two married adults with children; it is also a set of ideas about how the family as a social unit can and should be separated from outside intervention. Within this legal and cultural system, non-familial ways of organizing care, such as communal projects and mutual aid, remain unrecognized and de-legitimized based on ideologies that naturalize the family as the ideal form through which to provide care. In her history of American social policy against domestic violence, Elizabeth Pleck identifies three key beliefs about the ideal family that have driven American policymaking since colonial times: a belief in (1) the sanctity of domestic privacy, (2) conjugal and parental rights, and (3) the preservation of the family.

Of course, as the racial and class disparities in the family policing system demonstrate, Black and Brown families are largely treated as the exception to these white norms around family privacy, rights, and preservation. In turn, the family ideal has been used to protect some families from oversight and intervention while ensuring that others are surveilled and regulated. Yet people suffer on both sides of this dividing line, which was made heartbreakingly clear in the case of the six children who died at the hands of Jennifer and Sarah Hart. On the one hand, the children’s biological parents and aunt, who are Black, were put under close scrutiny by state child welfare agencies, stripped of their parental rights, and separated from their children. Meanwhile, the white couple who eventually adopted the children were not investigated even when the children sought outside help from neighbors after experiencing abuse and neglect. In the former case, the racialized family ideal made the children’s biological parents vulnerable to family policing, leading to the separation of the children from their parents. In the latter case, it cost the children their lives by protecting the Harts from outside intervention and concealing their abuse.

Policies designed to uphold the family ideal not only depend on and reinforce racial divisions; they also uphold class and gender disparities. For instance, despite the fact that, for the first time, fewer Americans are now married than unmarried, marriage continues to be rewarded through tax breaks. Yet, as benign as they may seem, marriage incentives have recently been criticized for the ways they contribute to racial, gender, and economic inequalities in America. According to a 2013 analysis, “over a lifetime, unmarried people can pay upward of $1 million more than their married counterparts for health care, taxes and more.” Married people also tend to have more flexibility in whether they work, in part due to employment benefits that enroll spouses as insurance beneficiaries, allowing them to drop in and out of the workforce as needed or seek out jobs that don’t provide full-time insurance.

The role of such policies in contributing to racial income gaps becomes clear when we look at marriage demographics, which show that in 2019, 31% of Black Americans and 67% of white Americans were married. In addition, Black women were even less likely than Black men to get married. Calls for Americans to resolve these disparities themselves by opting into marriage ignore the fact that marriage is not a universal ideal, nor is it equally accessible to everyone. The overwhelming evidence suggests that marriage is a response to, not a cause of, economic prosperity. High rates of marriage in the mid-20th century were made possible by economic policies that increased the middle class, and marriage rates have always been higher amongst Americans who have white-collar jobs and college and graduate degrees. These trends indicate that whether one gets married depends on structural and economic forces and not love or personal commitment alone. In addition, marriage—like all family traditions—is a product of institutional and cultural norms about what kinds of connections are valuable. As one family abolitionist put it: “What is ‘the family’ but a set of norms around gender, sexuality, household labor, and the pooling of resources for economic survival?”

The flip side of policies designed to reward those who fit into the family ideal are the “sticks” or punishments used to control the behavior of those who, whether by choice or circumstances, fall outside of it. In addition to experiencing discrimination in housing and immigration, single mothers are punished and coerced into precarious labor by welfare policies designed to make the receipt of welfare contingent on employment. Such policies treat the resources needed to sustain human life not as social rights but as “earned benefits.” Most of the parents who get caught up in the family policing system are also caught between (1) an under-regulated labor market that is designed to cut costs by minimizing guaranteed hours, requiring unpaid on-call work, and refusing benefits and (2) state policies that coerce them into this labor by reducing welfare benefits when parents work less.

Family policing abolitionists seek to upend this system of state-sanctioned exploitation in two key ways. First, instead of upholding the racialized family ideal, we seek to break down the border between public and private life, a border that is essential for capital accumulation and white domination. We do so by building community-based systems of care that will re-distribute the care-work that is currently loaded onto single parents and treated as a private cost. In this realm, we take inspiration from mutual aid projects that have grown in response to international crises as well as the grassroots efforts of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, which has continually worked to get fair wages for care-work on the federal agenda. Second, we push for policies that regulate employers instead of those that regulate families through surveillance and separation. This means organizing for living wages that pay for safe and comfortable housing, paid parental leave, and comprehensive childcare and healthcare. In other words, we work toward a world where human life—and all it takes to nurture it—is treated as a right, not just a resource.

Family policing abolitionists join a growing number of abolitionists who question who truly benefits from the institution of the family. Who benefits from the array of estate laws, inheritance laws, custody laws, tax credits, marriage incentives, and mandated reporting laws that maintain care and wealth as “private matters” in the US? Who benefits from the rhetoric that how families are formed (or torn apart) is a matter of personal choice or cultural preference rather than politics? By questioning the family ideal and the role of existing policies in systematically enforcing it, we begin to see not only the many ways that family policies perpetuate inequality, but also the myriad ways we might organize life and love beyond and perhaps even without the family.

Katie Gibson is a Post-Doctoral Teaching Fellow at the University of Chicago. As an ethnographer of youth-serving institutions, she has studied psychotropic drug use in Illinois’s foster care system, case managers’ interpretations of the federal mandate to ensure child “well-being,” and advocacy practices amongst a youth-led policy coalition in California. She is also a former ward of the state of New York.

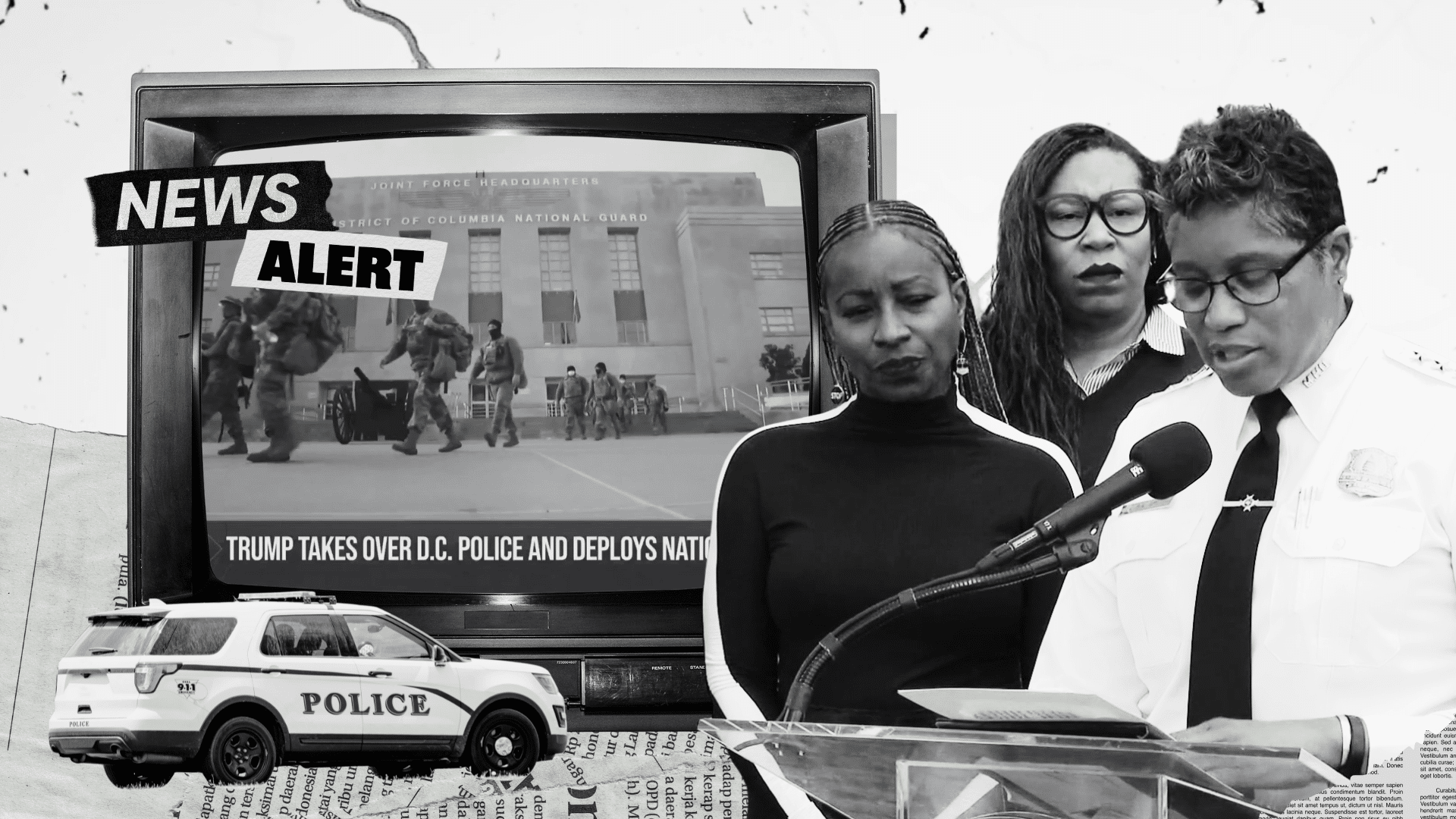

The current “takeover” of DC has led to federal agents terrorizing DC’s majority Black neighborhoods.

Five years ago, around Juneteenth—a celebration of delayed but hard-won freedom—a small collective of insiders-turned-abolitionists planted the seeds of upEND.